In the 3rd edition of the Barnett/Blackman Constitutional Law Casebook, we are reproducing Justice Holmes’s draft dissent from Buchanan v. Warley. When I first taught this case, I was surprised to see Justice Holmes go along with the Lochner-style due process analysis of the majority. After some research, which I blogged about in 2013, I discovered that Holmes in fact had circulated a draft dissent that did not get any joins.

Eleven days before the opinion was released, Holmes was still on the fence. Ultimately, he decided to withdraw his dissent. Professors David E. Bernstein and Ilya Somin speculate that Holmes did not change his mind on the merits, but rather, because “could not get a second vote.” I agree.

A copy of Holmes’s draft was reproduced in Volume 9 of History of the Supreme Court of the United States: The Judiciary and Responsible Government by Alexander M. Bickel & Benno C. Schmidt, Jr. (1984). This opinion, which does not appear in any other constitutional law casebook of which we are aware, provides further insights into Justice Holmes’s views on the Due Process Clause—even where all of his colleagues disagree.

—

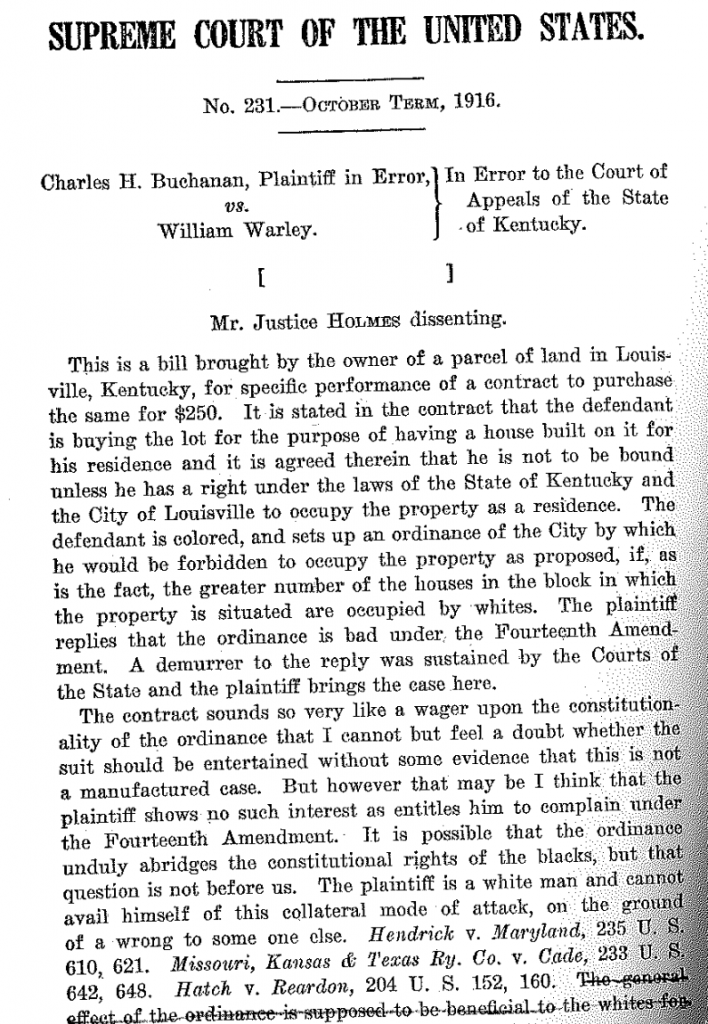

Supreme Court of The United States

No. 231. October Term, 1916.

Charles H. Buchanan, Plaintiff in Error,

Vs.

William Warley.

In Error to the Court of Appeals of the State of Kentucky.

Mr. Justice Holmes dissenting.

This is a bill brought by the owner of a parcel of land in Louisville, Kentucky, for specific performance of a contract to purchase the same for $250. It is stated in the contract that the defendant is buying the lot for the purpose of having a house built on it for his residence and it is agreed therein that he is not to be bound unless he has a right under the laws of the State of Kentucky and the City of Louisville to occupy the property as a residence. The defendant is colored, and sets up an ordinance of the City by which he would be forbidden to occupy the property as proposed, if, as is the fact, the greater number of the houses in the block in which the property is situated are occupied by whites. The plaintiff replies that the ordinance is bad under the Fourteenth Amendment. A demurrer to the reply was sustained by the Courts of the State and the plaintiff brings the case here.

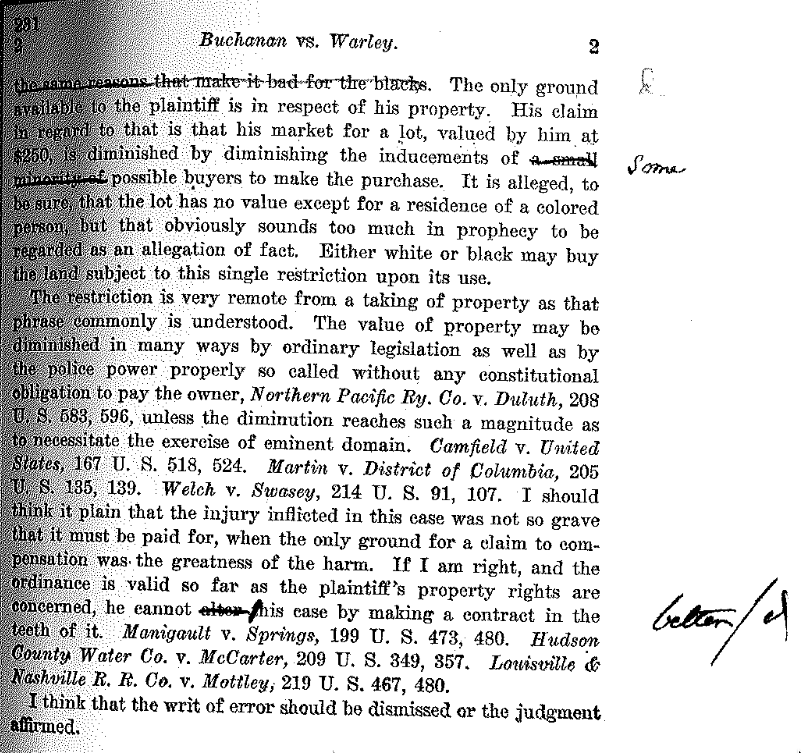

The contract sounds so very much like a wager upon the constitutionality of the ordinance that I cannot but feel a doubt whether the suit should be entertained without some evidence that this is not a manufactured case. But, however that may be I think that the plaintiff shows no interest as entitles him to complain under the Fourteenth Amendment. It is possible that the ordinance unduly abridges the constitutional rights of the black, but that question is not before us. The plaintiff is a white man and cannot avail himself of the collateral mode of attack, on the ground of a wrong to some one else. Hendrick v. Maryland, 235 U. S. 610, 621. Missouri, Kansas & Texas Ry. Co. v Cade, 233 U. S. 642, 648. Hatch v. Reardon, 204 U. S. 152, 160. The general effect of the ordinance is supposed to be beneficial to the whites for the same reasons that made it bad for the blacks. [Eds.—this sentence was crossed out by hand in Holmes’s draft.] The only ground available to the plaintiff is in respect of his property. His claim in regard to that is that his market for a lot, valued by him at $250, is diminished by diminishing the inducements of a small minority of [Eds.—“a small minority of” is crossed out by hand, and “some” is handwritten in the margin] possible buyers to make the purchase. It is alleged, to be sure, that the lot has no value except for a residence of a colored person, but that obviously sounds too much in prophecy to be regarded as an allegation of fact. Either white or black may buy the land subject to this single restriction upon its use.

The restriction is very remote from a taking of property as that phrase commonly is understood. The value of property may be diminished in many ways by ordinary legislation as well as by the police power properly called without any constitutional obligation to pay the owner, Northern Pacific Ry. Co. v Duluth, 208 U. S. 583, 596, unless the diminution reaches such a magnitude as to necessitate the exercise of eminent domain. Camfield v. United States, 167 U. S. 518, 524. Martin v. District of Columbia, 205 U. S. 135, 139. Welch v. Swasey, 214 U. S. 91, 107. I should think it plain that the injury inflicted in this case was not so grave that it must be paid for, when the only ground for a claim to compensation was the greatness of the harm. If I am right, and the ordinance is valid so far as the plaintiff’s property rights are concerned, he cannot alter [Eds.—“alter” is crossed out by hand, and “better” handwritten in margin) this case by making a contract in the teeth of it. Manigault v. Springs, 199 U. S. 473, 480. Hudson County Water Co. v. McCarter, 209 U.S. 349, 357. Louisville & Nashville R. R. Co. v. Mottley, 219 U.S. 467, 480.

I think that writ of error should be dismissed or the judgment affirmed.