Back in January, when the President announced his long-awaited executive action on guns, the general consensus was that the steps he took were underwhelming. Not so. As I explained in National Review, President Obama was taking the long game on gun control. The key action he took focused on promoting research into so-called “smart guns.”

Beyond expanding the scope of prohibited gun owners, the president’s executive action also has the potential to restrict the types of guns people can buy. One of his executive orders directs the federal government to “promote the use and acquisition of new [gun] technology.” These so-called “smart guns” require a fingerprint scanner or a radio-frequency identification tag to be near the gun, before it will fire. During his press conference, the president joked, “If we can set it up so you can’t unlock your phone unless you’ve got the right fingerprint, why can’t we do the same thing for our guns?”

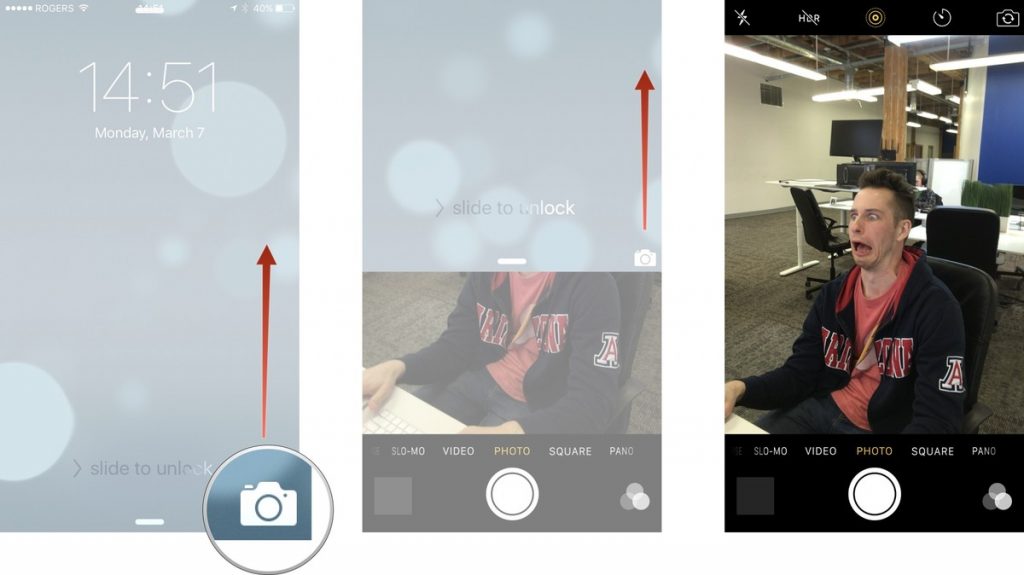

Let me digress for a moment on the smartphone-fingerprint example. On the iPhone, there is a feature that allows you to take a picture without having to use a fingerprint, or code to unlock the phone.All you have to do is swipe up with the camera icon, and it goes straight to the camera app. Why do you think Steve Jobs and company inserted that feature? Because if you enter the wrong code, or if your finger is sweaty, the phone doesn’t unlock right away. When you have to take a selfie at *just* the right moment, and seconds count, requiring the user to unlock the phone takes too much time.

If time is of the essence to take a selfie, then time is really of the essence when using a firearm for self-defense. Even if a smart gun is able to discern the owner’s fingerprints, or the owner’s grip, it still introduces a potential for error. With self-defense, every millisecond counts.

The usual response to this is that the risk of malfunction is outweighed by the potential of eliminating accidental shootings. Politico explains:

It wouldn’t prevent most mass shootings, gun crimes or suicides — currently the biggest driver of gun deaths. However, they could cut down on the roughly 500 deaths each year from accidental shootings, especially by kids. Advocates also point to findings that most youth suicides are committed with a parents’ weapon, and instances where officers’ own guns are stolen in a scuffle and used to shoot them cause about 1 in 10 police deaths.

I address the magnitude of accidental shootings, in comparison to other deaths, in The Shooting Cycle.

A related heuristic focuses on how people weigh unfamiliar events. This heuristic is more intuitive: the fear of the unknown is greatest. More precisely, people often overweigh the risk of unfamiliar events. Consider the related topic of accidental shootings of young children (primarily where a child uses the firearm to kill him or herself). Though these events are horrible and avoidable tragedies, like mass shootings, they are also uncommon. Professor Dan Kahan’s observations, which are not limited to children, show that there are on average fewer than 1,000 accidental gun homicides per year.60 In comparison, there are roughly 3,500 drowning deaths per year.61

When looking specifically at the causes of death of children, the ratios are roughly similar. In 2010, children ages one to fourteen were more than three times as likely to die by unintentional drowning than by becoming the victims of a homicide by firearm.62 We stress, as does Professor Gary Kleck, that “[t]he point is not that guns are safe because they cause accidental death less often than” more familiar causes, such as drownings, but to provide a “meaningful point of reference.” 63

…

In contrast, when people make choices from familiar experiences, so called “decisions from experience,” they underweigh the probability of rare events.66 In other words, people will underweigh the risk of something they are familiar with—for example, death by drowning in a pool. After all, most people have been in a pool, seen a lifeguard, and are aware of the possibility of children drowning. But, they will overweigh the risk of something they only learn about from descriptions—such as media reports about death by firearm violence. These are rare tragedies that (thankfully) impact very few people personally.

Anyway, back to the smart guns. The problem with these high-tech gadgets is that many states have enacted laws that would criminalize the sale of non-smart guns once smart guns become commercially viable. As I noted in National Review in January:

This is not a laughing matter. In 2002, New Jersey enacted a law that said when “personalized handguns are available,” only smart guns could be sold in the Garden State. To date there simply hasn’t been a market for these weapons. However, as NPR reported, if federal agencies purchase these smart guns in large quantities, it would increase their availability nationwide and trigger the New Jersey law. Other states could enact similar laws to the Garden State’s and lead to a massive prohibition on all arms that are not smart.

And that is precisely the goal of encouraging law enforcement agencies to research and acquire these weapons–provide manufacturers with enough incentives to create them, thus triggering the smart-gun laws. But there is a wrinkle here. Police officers don’t want the guns for the same reason law-abiding gun owners don’t want them–they are not 100% reliable.

“Police officers in general, federal officers in particular, shouldn’t be asked to be the guinea pigs in evaluating a firearm that nobody’s even seen yet,” said James Pasco, executive director of the Fraternal Order of Police. “We have some very, very serious questions.”

Pasco said he’s already been vocal about his concerns in private conversations with administration officials and he plans to keep up the drumbeat even as he waits for an official announcement. …

Pasco compared the push for smart guns to the decision to limit local departments’ access to surplus military equipment.

“They sit down among themselves and decide what is best for law enforcement, but from a political standpoint, and then tell officers they’re doing it for their benefit,” Pasco said.

Of the 330,000 officers in his union, Pasco said, “I have never heard a single member say what we need are guns that only we can fire,” noting that there might be moments in close combat when an officer would need to use a partner’s weapon or even the suspect’s.

These same concerns apply equally to law-abiding gun owners who want a reliable firearm that can fire under less-than-ideal circumstances in short order.

There was an additional announcement buried at the bottom of the Politico piece:

Obama also ordered the Social Security Administration to start writing regulations that could bar some beneficiaries from buying a gun if they’ve been deemed mentally incapacitated. It could face a legal challenge, depending on the final wording, and advocates who work closely with the White House anticipate those details could come out on Friday, too.

This development is perhaps even more significant than the smart-guns initiative, because it can have the effect of disarming without due process millions of Americans on social security.

Update: NPR has a piece about why police want nothing to do with a smart gun:

ROSE: But almost right away, Zilkha discovered that the customers he imagined were not as enthusiastic as he was. Let’s start with police. Stephen Albanese is a retired New York City police officer.

For 20 years, it was his job to make sure the department’s guns worked like they were supposed to. Albanese says he and other officers weren’t sure they could trust smart guns to fire every time.

STEPHEN ALBANESE: I’ve had cops tell me that their worst nightmare is getting involved in a situation, pulling out that gun, pulling the trigger and hearing it go click.

The same principle applies to law-abiding citizens. Deciding to use lethal force for self-defense is a decision must be made in an instant. Hesitating too long because the gun won’t fire would prevent a person from defending himself.