The Yale Journal asked Judge Richard Posner to re-review William Eskridge’s 1996 Book, The Case for Same-Sex Marriage. In his initial review in 1997, Posner rejected the right to same-sex marriage as a constitutional matter. Seventeen years later, Posner wrote the 7th Circuit’s decision in Baskin v. Bogan, invalidating the marriage laws of Indiana and Wisconsin. What happened in those intervening 17 years? Posner’s essay discusses his personal evolution, and the evolution of the United States. As alway, Judge Posner’s candor, and willingness to say where he erred, is admirable. But his discussion–and indeed rejection–of constitutional law is far less admirable, in light of his reliance on constitutional law to invalidate the marriage laws.

In the re-review, Posner echoed comments he made earlier this month at Loyola Law School in Chicago, about how the text of the Constitution is largely irrelevant.

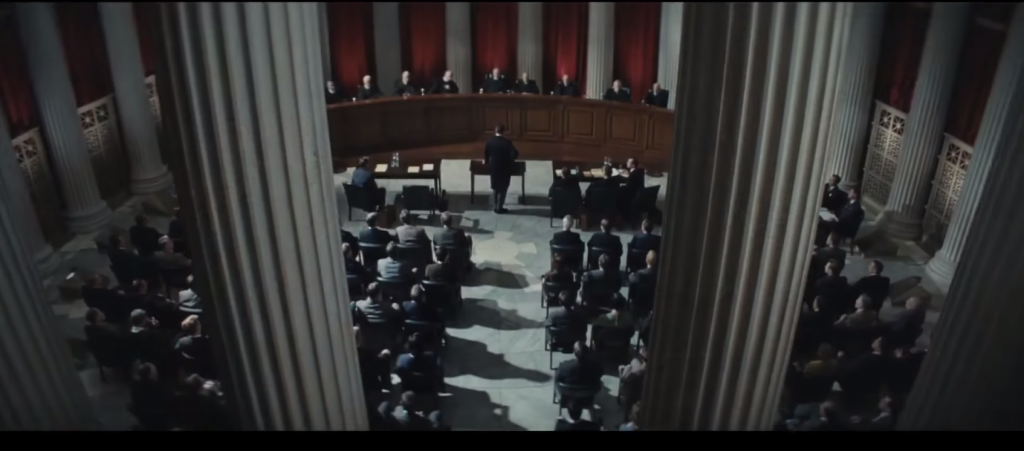

My same-sex marriage case, Baskin v. Bogan, invalidating as I said earlier the Indiana and Wisconsin prohibitions of same-sex marriage, was argued in August 2014 and decided in September, just months before Obergefell. By the summer of 2014, the tide was running strongly in favor of invalidating such prohibitions, although it was not certain that the Supreme Court would go with the tide. I do think the change in public opinion was decisive for all the courts that ruled in favor of creating a constitutional right to same-sex marriage. Law is not a science, and judges are not calculating machines. Federal constitutional law is the most amorphous body of American law because most of the Constitution is very old, cryptic, or vague. The notion that the twenty-first century can be ruled by documents authored in the eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries is nonsense.

One would think then, that Posner’s decision in Bogan would be bereft of any citations to those “old, cryptic, or vague” provisions of the Constitution, including the 14th Amendment. But that is not the case, as the opinion is grounded in the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. Here are a few of the key sentences from the decision:

In light of the foregoing analysis it is apparent that groundless rejection of same-sex marriage by government must be a denial of equal protection of the laws, and therefore that Indiana and Wisconsin must to prevail establish a clearly offsetting governmental interest in that rejection. …

A degree of arbitrariness is inherent in government regulation, but when there is no justification for government’s treating a traditionally discriminated-against group significantly worse than the dominant group in the society, doing so denies equal protection of the laws. …

If no social benefit is conferred by a tradition and it is written into law and it discriminates against a number of people and does them harm beyond just offending them, it is not just a harmless anachronism; it is a violation of the equal protection clause, as in Loving. …

Yet withholding the term “marriage” would be considered deeply offensive, and, having no justification other than bigotry, would be invalidated as a denial of equal protection.

Why did Posner base his decision on a parchment barrier whose relevance is “nonsense”? Because, by his own admission, he has no problem looking to text and history after he has made up his mind of how he is going to rule. As he said at Loyola:

The time to look at precedent, statutory text, legislative history, that’s after you have some sense of what is the best decision for today. Then you ask whether it is blocked by something that happened in the past. That’s all I have to say.

If the 14th Amendment is “old, cryptic, or vague,” it can’t conceivably block whatever the “best decision for today” is, including a right to same-sex marriage.

But wouldn’t it be more forthright if Posner eschewed the anchor of “equal protection,” and instead wrote that marriage laws simply were not “sensible”? By his own admission, that is the correct test of constitutional analysis:

I think we can forget about the 18th century, much of the text. We ask with respect to contemporary constitutional issues, ask what is a sensible response.

At bottom, Posner candidly rejects any fidelity to the text of the Constitution. That invariably includes, of course, the parchment barrier that allows him to append the honorific “Judge” to his name. Yes, Richard Posner’s powers derive not from his boundless intellect, but from the bounds of Article III. Four aspects of the Constitution are particularly salient.

First, what is the “judicial power”? Is that phrase not “vague”? Marbury v. Madison is not self-evident. Does the text in any manner suggest that unelected judges can invalidate the laws enacted by the states, and that have been in existence for millennia? Is that a “sensible” reading of a “vague” provision of the Constitution?

Second, how long can these judges serve? Posner explained that the 7th Amendment’s $20 amount-in-controversy requirement should not be enforced because it is “absurd” in light of inflation: $20 means something very different in 1789 and 2015.

There are things that are in the text of the Constitution that are absurd. One is the idea that if the matter in controversy is at least $20, you have the right to a jury trial. That is absurd. $20 in the 18th century meant something very different than in the 21st century. What the Supreme Court should say when people bring jury cases for $20 is that provision is archaic and will not be enforced.

Know what else is “absurd” two centuries later? That a provision guaranteeing life-tenure when the average lifespan was about 40 should also guarantee life-tenure when the average lifespan is over 80. No other state, or western nation for that matter, creates a permanent sinecure for all-powerful jurists. A more “sensible” provision would be to limit judges to specific terms, or impose a mandatory retirement age. At the margins, we may disagree on what that term ought to be. Maybe some say 15 years, some say 25 years, or retirement at 75, but certainly there is a “sensible number” to be chosen. But in any case, 30 years is far too long. That stretches across five presidencies. Judge Posner, 76-years-young, was confirmed in 1981, and is in his 34th year of service. By Judge Posner’s own reasoning, his commission, and license to invalidate democratically-enacted laws, should “not be enforced.”

Third, even if you think the Constitution is irrelevant, the oath that allows a judge to assume the office to interpret the Constitution is in the Constitution.

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution

Posner, a “judicial Officer” of the United States, took an oath to “support this Constitution.” Opinions he write are not binding by dint of their persuasiveness alone, but because he has the word “Judge” before his name. (And even then, the Justices above him are not so bound, because they hold a different office).

Finally, we should not forget that the Constitution doesn’t actually guarantee life tenure–only service during “good behaviour.” Personally admitting that being bound by that charter is “nonsense” seems flatly inconsistent with the very oath he took–indeed, an oath from the document that grants him the very power to be a judge. The $20 provision in the 7th Amendment is clear as day. If $20 doesn’t mean $20, then “good behaviour” can’t really mean “good behaviour.” Maybe, at a minimum, it means trying your best to follow the Constitution, not ruling however you think is “sensible.”

I could go on and on, but you get the point. I admire Judge Posner’s candor about rejecting the Constitution as a binding document. As an academic theory, his pragmatism offers a powerful rejoinder to other formalistic theories. But he isn’t just writing as a scholar. He practices what he preaches, and strikes down laws on that basis. If he truly believes what he believes, then he ought not to use that same nonsensical Constitution as his license to invalidate democratically enacted laws. You can’t have your Constitution, and eat it too.