Teaching Brown v. Board of Education is an interesting experience. Most of my students come into constitutional law knowing, maybe 2 or 3 cases by name–Brown v. Board, Roe v. Wade, and perhaps Bush v. Gore. Students always expect Brown v. Board to be a broad pronouncement of equality under law. And then they read it, and are utterly disappointed. It is a fairly narrow opinion, that leaves a lot to be desired.

One of the most underwhelming aspects is its heavy reliance on social science research in the now-famous Footnote 11:

Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority. K. B. Clark, Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development (Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth, 1950); Witmer and Kotinsky, Personality in the Making (1952), c. VI; Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effects of Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion, 26 J. Psychol. 259 (1948); Chein, What are the Psychological Effects of [347 U.S. 483, 495] Segregation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities?, 3 Int. J. Opinion and Attitude Res. 229 (1949); Brameld, Educational Costs, in Discrimination and National Welfare (MacIver, ed., (1949), 44-48; Frazier, The Negro in the United States (1949), 674-681. And see generally Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944).

At the New York Times Upshot Blog, historian Michael Bechloss has a feature on the study by Dr. Clark, which asked children to play with black and white dolls.

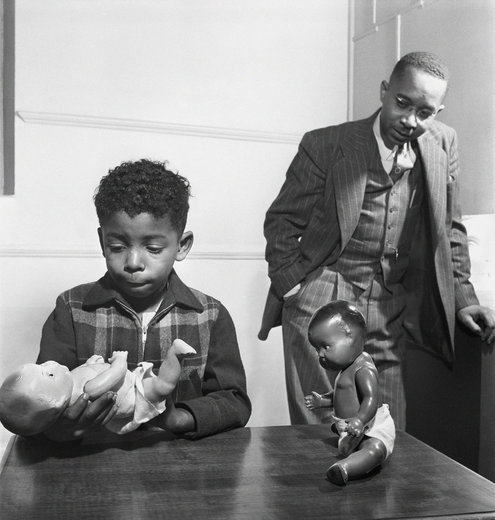

The social psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark sought to challenge the court’s existing opinion that “separate but equal” public schools were constitutional (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896) by testing whether African-American children were psychologically and emotionally damaged by attending a segregated school.

As Kenneth Clark recalled in 1985, he would produce white and black dolls and say, “Show me the doll that you like to play with … the doll that’s a nice doll … the doll that’s a bad doll.”

A majority of the African-American children from segregated schools rejected the black doll. By Dr. Clark’s account, when those boys and girls were then told, “Now show me the doll that’s most like you,” some became “emotionally upset at having to identify with the doll that they had rejected.” Some even stormed out of the room.

As Dr. Clark recalled, he and his wife concluded that “color in a racist society was a very disturbing and traumatic component of an individual’s sense of his own self-esteem and worth.”

Here is a photograph from the experiment.

And, Bechloss has an excellent anecdote about Thurgood Marshall, who argued Brown:

As late as the early 1950s, social science findings did not often cross the radar screen of the nation’s highest court. But during preparations for the cases that made up Brown, the N.A.A.C.P. chief counsel (later Supreme Court Justice) Thurgood Marshall dismissed warnings by other civil rights lawyers that the justices would be offended if they were subjected to tales about dolls and wailing children.

In May 1954, he was proved right. When Brown was decided, the court cited the doll study as a factor in its deliberations. That night, at an exuberant dinner, Mr. Marshall raised a glass to Kenneth Clark and demanded of those once-skeptical colleagues, “Now, apologize!”