This year, the Harlan Institute and ConSource have partnered to sponsor the 2014 Virtual Supreme Court Competition, focusing on NLRB v. Canning. For those interested, here is the lesson plan. Any interested teachers should sign up and encourage their students to participate. The grand prize is a trip to Washington for Constitution Day 2014.

National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning Corporation

Certiorari granted by the United States Supreme Court on June 24, 2013

Oral arguments scheduled TBD

Outline:

The Parties

Petitioner: The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)  |

v. |

Noel Canning Corporation |

(jump to the top of the page)

The Questions Presented

(jump to the top of the page)

Case Background

The National Labor Relations Board

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) requires that employers and labor unions follow certain procedures governing labor relations. Disputes over violations of the NLRA are heard by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The NLRB is governed by five members who serve five-year terms. Each member is nominated by the President, and confirmed by the Senate. Under the rules of the NLRA, the NRLB can only make a decision if three members are present. This is known as a quorum. If only two members issue a decision, a quorum is lacking, and the decision is void.

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) requires that employers and labor unions follow certain procedures governing labor relations. Disputes over violations of the NLRA are heard by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The NLRB is governed by five members who serve five-year terms. Each member is nominated by the President, and confirmed by the Senate. Under the rules of the NLRA, the NRLB can only make a decision if three members are present. This is known as a quorum. If only two members issue a decision, a quorum is lacking, and the decision is void.

The Recess Appointment

The Noel Canning decision arose in the context of an ongoing struggle between presidents and Congress over the use of the President’s recess appointments power. The Constitution gives the President the power “to fill up all vacancies that may happen during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session.” (Article II, Section 2).

In 2007, the Democrats regained control of the Senate. In order to avoid allowing the Senate to begin a recess, where President George W. Bush could appoint a recess nominee, the Democrats began the practice of conducting so-called “pro forma sessions,” during which the only business conducted is a simple call to order, often by a single senator. Some senators argued that the pro forma sessions converted an otherwise lengthy recess into a shorter adjournment, which would be too brief to trigger the president’s recess appointments power.

In 2010, President Obama appointed Craig Becker to the NLRB via his recess appointments power. When he resubmitted the nomination at the beginning of the Congress’s next term, Senate Republicans filibustered (a parliamentary procedure where debate is extended, allowing one or more members to delay or entirely prevent a vote) the candidate, while also preventing a vote on a second nominee, Terrence F. Flynn.

The expiration of the 2010 Becker recess appointment threatened to reduce the Board’s membership to two. President Obama, in turn, withdrew Becker’s nomination and forwarded to the Senate two new nominations. The Senate failed to act on these nominations by the end of the first session of the 112th Congress. On January 4, 2012, President Obama set the stage for Noel Canning v. NLRB by giving recess appointments to three NLRB nominees.

The National Labor Relations Board Decision

The Noel Canning Corporation, which bottles soda and other products in Washington, had a dispute with their union regarding a collective bargaining agreement. The union filed a complaint with the NLRB, and the NRLB found that Canning violated the National Labor Relations Act.

The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals

Noel Canning appealed the NLRB decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. In its January 25, 2013 decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit held that while the NLRB’s decision was legally supportable, it could not be enforced, because President Obama’s recess appointments were invalid, and without them the NLRB lacked the necessary quorum to conduct business.

In issuing this decision, the court drew two conclusions, the former unanimously agreed upon, and the latter by a 2-1 vote. First, the President can only make appointments during a break between sessions. Based on the 18th century (the century in which the Constitution was drafted and ratified) reading of the phrase “the recess,” the President can only validly make recess appointments during the period of adjournment between two sessions of Congress, and not during any other mid-session break, or intra-session recess. The court unanimously agreed on this point.

Second, the President can only fill vacancies that arose during the recess. In other words, if an official left office while the Congress was in recess, the President could fill that position. Based on the 18th century understanding of “happen” in the Recess Appointments Clause was “to occur,” and, thus, the clause, properly read, only allows the President to fill those vacancies that first arise during recesses between sessions of Congress. This position split on a 2-1 vote.

Judge Griffith in his concurrence argued that the court should not have reached this conclusion, because the court’s holding on intra-session recesses was sufficient to vacate the NLRB’s decision. Judge Griffith counseled judicial restraint, stating “[the court] should not dismiss another branch’s longstanding interpretation of the Constitution when the case before [it] does not demand it.”

The Law

Read the Text & History of the Constitution and Decide if You Agree with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

The President’s Appointment Power

Constitutionally, the President is entrusted with the power to appoint officials to a variety of positions. Ambassadors, public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States are appointed to office by the President and with the advice and consent (approval) of the Senate. The Congress may by law allow the President alone, courts of law, or heads of Executive Departments to make appointments of certain inferior officers. The Constitution does not define what is meant by “inferior officers.”

“[The President] shall nominate, and, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.”

The concept of “Advice and consent” was a popular idea in American political thought from the Revolution through the Articles of Confederation. Many early state constitutions either limited the executive power of their chief officers with a council of advisers or gave some executive authority, such as the appointment power, to state legislatures.

- Maryland’s 1776 Constitution delineated appointment power as unitarily held by the state legislature, the General Assembly. The Governor had power to fill only a few vacancies, and these he would fill in accordance with the advice of his Council.

- Pennsylvania sharply limited executive power in its 1776 Constitution; although the legislature’s executive council elected a president and vice president, these officers were practically powerless. In some cases, the executives of the state could exercise their authority on their own, but these instances were limited to the issuing of trade embargoes.

- Ratified in 1778, South Carolina’s Constitution mandated that the state legislature would elect the Governor and that the Governor could only appoint officials with the “advice and consent” of his Privy Council. Similar to the Pennsylvania Constitution, the Governor could exercise limited power in the recess of the legislature, but this power was also limited to trade embargoes.

When issue of government appointments was taken up at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the opinion of the delegates was divided; the convention was deadlocked in deciding whether or not appointment power should be unitarily vested in the President. Alexander Hamilton successfully broke this deadlock by proposing the jointly held appointment power model that is represented in the Constitution.

During his tenure as President, George Washington set a standard for making appointments by which the President would exercise leadership while the Senate’s consent completed the process (Washington, letter to Senate Committee on Treaties and Nominations, Aug. 10, 1789).

The President’s Recess Appointment Power

With respect to vacant positions that occur during recesses of the Senate, when their “advice and consent” is not available, the President is empowered to appoint officials to fill these vacancies. The “Recess Appointments Clause” addresses this power:

“The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.”

The definition of a “recess appointment” and the scope of executive power to make these appointments were concepts formed over a number of years. In the Revolutionary era, the majority of state constitutions allowed for their executive officers to make decisions while the legislature was not in session, but these actions were temporary, and would typically expire at the end of the legislature’s next session, unless the legislature approved of the action:

In its 1776 Constitution of North Carolina, for example:

“XX. That in every case where any officer, the right of whose appointment is by this Constitution vested in the General Assembly, shall, during their recess, die, or his office by other means become vacant, the Governor shall have power, with the advice of the Council of State, to fill up such vacancy, by granting a temporary commission, which shall expire at the end of the next session of the General Assembly…” North Carolina Constitution, Art. XX

While unanimously approved by the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, the Recess Appointments Clause was subject to further debate during the ratification period and thereafter. Federalists, members of the political faction supporting the Constitution’s ratification, argued that the recess appointment power was a stopgap measure to ensure the continued efficient operation of the government. However, Anti-Federalists, who were against ratification, contended that this ability was an unjust manipulation of circumstances to give the President a tyrannical share of power.

The modern debate over the power of presidents to make recess appointments focuses on the issue of whether the President’s recess appointment power applies not only to inter-session recesses, when the Senate adjourns between sessions, but also intra-session recesses, when the Senate takes short breaks during its sessions.

The Senate’s Role in the Appointments Process

The Senate’s power to provide “advice and consent” is an important powers granted to Congress in the Constitution. In this capacity, the Senate serves as an advisory group for the President when s/he is making treaties or appointing government officials.

“[The President] shall nominate, and, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.”

Practically speaking, this means that the Senate has the power to approve the President’s nominees for open positions. As exemplified above in the sampled state constitutions, this division of appointment power was founded in the suspicion of executive power that was common in the Revolutionary era. The Drafters of the Constitution were wary of skewing power towards any one branch of government. Thus, giving the Senate “advice and consent” power ensures that the President is not the only authority involved in the vetting and appointment of candidates for important executive positions and federal judgeships.

Long considered an important feature of the checks and balances based political structure that would later become the hallmark of the American system, many early state legislatures were constitutionally empowered to make appointments on their own in order to limit the influence of state executives.

State constitutions drafted and ratified when the country was governed by the Articles of Confederation sharply circumscribed the role of executives in exercising the power to appoint officials on account of the then-widespread fear of centralized power and executive tyranny. This fear was borne out of experience with the British crown and his royal governors.

The Constitutional Convention on the Appointment Process

When the Constitutional Convention of 1787 met to draft the Federal Constitution, the delegates, encouraged by Alexander Hamilton, decided on the current appointments arrangement presented in the Constitution.

Hamilton had proposed this plan as a means of compromise in order to break the deadlocked debate on the issue. He elaborated this concept in Federalist No. 77, giving both the President and the Senate a share in the appointment power ensured that no branch would have unitary control over the process.

Hamilton contended, and subsequent interpreters of the Constitutional arrangement would agree, that the House of Representatives was to have no role in the appointment process. As he noted in Federalist No. 77:

“A body so fluctuating, and at the same time so numerous, can never be deemed proper for the exercise of that power. Its unfitness will appear manifest to all . . . All the advantages of the stability, both of the executive and of the senate, would be defeated by this union; and infinite delays and embarrassments would be occasioned. The example of most of the states in their local constitutions, encourages us to reprobate the idea.”

However, should the House want to indirectly involve itself in the appointment process, it can influence the Senate’s action by withholding its power of consent over the Senate’s ability to adjourn for a recess. (Article I, Section 5).

This tactic forces the Senate to stay in session while taking intermittent three-day recesses (called a pro-forma session) and would ostensibly prevent the President from making a recess appointment because of the modern convention that a “recess” is at minimum a duration of four days. The constitutionality of the use of a “recess appointment” by a President during a pro-forma session is one of the issues being considered in National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning Company (Jonathan Allen, “Senators ask John Boehner to Help Block Obama Recess Appointments”).

(jump to the top of the page)

Primary Sources – The History

What is the original meaning of the recess appointments clause?

We provide six primary sources in favor of a narrow interpretation of the recess appointment clause. These sources suggest that the President’s recess appointments were not valid. We provide five primary sources in favor of a broad interpretation of the recess appointment clause. These sources suggest that the President’s recess appointments were valid.

In support of a narrow interpretation of the clause

1. Letter from Samuel Adams to Arthur Lee (Oct. 31, 1771)

In a letter to Arthur Lee, Samuel Adams details the Governor of Massachusetts’ practice of postponing certain executive business until sessions of the General Court had concluded and the disagreeing Councilors had left the city. At this point, the Governor would enact controversial measures and make appointments without having to worry about opposition from the Council. Adams went on to detail a lengthy list of recent appointments and their personal connections to the governor.

“With regard to the Council, it is hardly possible for any one at a distance to ascertain their political Sentiments from what they see of their determinations publishd [sic] here in general, for it has been the practice of the Governor to summon a general Council at the Time when the Assembly is sitting & of Course the whole Number of Councillors [sic] is present—but in their Capacity of Advisers to the Governor they are adjournd [sic] from week to week during the Session of the Assembly & till it is over when the Country Gentlemen Members of Council return home. Thus the general Council being kept alive by Adjournments, the principal & most important part of the Business of their executive department is done by seven or eight who live in & about the Town, & if the Governor can manage a Majority of s small a Number, Matters will be conducted according to his mind. I believe I may safely affirm that by far the greater Number of civil officers have been appointed at these adjournments; so that it is much the same as if they were appointed solely by our ostensible Governor or rather by his Master, the Minister for the time being.”

2. Letter of Cato IV (July 3, 1789)

Here, Cato, presumably New York governor, George Clinton, expresses his concern regarding the extent of the President’s power in the legislature’s recess.

“Though the president, during the sitting of the legislature, is assisted by the senate, yet he is without a constitutional council in their recess- he will therefore be unsupported by proper information and advice, and will generally be directed by minions and favorites, or a council of state will grow out of the principal officers of the great departments, the most dangerous council in a free country…”

3. Letter from George Washington to William Drayton

In November 1789, George Washington wrote William Drayton, informing Drayton of his appointment as a federal judge in the district of South Carolina. Washington expressed that he was acting under his constitutional recess appointment power and that he had the utmost confidence that his various recess commissions would be promptly confirmed upon the Senate’s return to session.

“Sir. The Office of Judge of the district Court in and for South Carolina District having become vacant; I have appointed you to fill the same, and your Commission therefore [sic] is enclosed. You will observe that the commission which is now transmitted to you is limited to the end of the next Session of the Senate of the United States. This is rendered necessary by the Constitution of the United States, which authorizes the President of the United States to fill up such vacances [sic] as may happen during the recess of the Senate—and appointments so made shall expire at the end of the ensuing Session unless confirmed by the Senate; however there cannot be the smallest doubt but the Senate will readily ratify and confirm this appointment, when your commission in the usual form shall be forwarded to you.”

4. Edmund Randolph, Opinion on Recess Appointments for President Jefferson (July 7, 1792)

Much confusion surrounded Washington’s ability to use his recess appointments power to fill the position of Chief Coiner to the United States Mint, an office created by an April 1792 statute, and one for which the Senate had not made a nomination prior to its recess. In response to this confusion, Attorney General Randolph wrote Thomas Jefferson, then Washington’s Secretary of State, expressing his belief that Washington could not use his recess appointments power under these circumstances.

“The question is, whether the President can, constitutionally, during the new recess of the Senate, grant to a chief Coiner a Commission which shall expire at the end of their next session. Is there a vacancy in the office of chief Coiner? An office is vacant when no officer is in the exercise of it. So that it is no less vacant when it has never been filled up, that it is upon the death or resignation of an incumbent. The office of Chief Coiner is therefore vacant. But is the vacancy one which has happened during the recess of the Senate? It is now the same and no other vacancy, than that, which existed on the 2nd of April 1792. It commenced therefore on that day or may be said to have happened on that day. The Spirit of the Constitution favors the participation in the Senate in all appointments. But as it may be necessary oftentimes to fill up vacancies, when it may be inconvenient to summon the senate a temporary commission may be granted by the President…For lthough’ [sic] I am well aware, that a chief Coiner for satisfactory reasons could not have been nominated during the last session of the Senate; yet every possible delicacy ought to be observed in transferring power from one order in government to another.”

5. Letter from Alexander Hamilton to James McHenry (May 3, 1799)

Following John Adams’ letter expressing his belief in his ability to use his recess appointments power to fill a vacancy happening during a Senate session, Secretary of War McHenry wrote Alexander Hamilton to inquire about the powers of the Recess Appointments Clause. Here, Hamilton expresses his disagreement with Adams’ previously described interpretation of the Clause. Note that at this time a schism existed in the Federalist partisan alliance between those supporting Adams and those supporting Hamilton.

“After mature reflection on the subject of your letter of the 26th of last month; I am clearly of opinion that the President has no power to make alone the appointment of Officers to the Batalion [sic]…In my opinion Vacancy is a relative term, and presupposes that the Office has been once filled. If so, the power to fill the Vacancy is not the power to make an original appointment. The phrase “Which may have happened” serves to confirm this construction. It implies casualty—and denotes such Offices as having been once filled, have become vacant by accidental circumstances. This at least is the most familiar and obvious sense, and in a matter of this kind it could not be adviseable [sic] to exercise a doubtful authority. It is clear, that independent of the authority of a special law, the President cannot fill a vacancy which happens during a session of the Senate.”

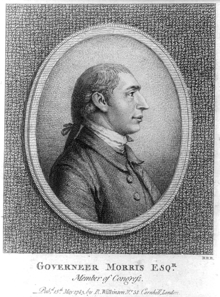

6. Letter from Gouverneur Morris to W.H. Wells (February 2, 1815)

In this letter, Morris both questions the amount of power given to the President under the Recess Appointment Clause at the Constitutional Convention and reflects on a personal challenge he had leveled on the subject.

The Constitution, I think, intended that certain offices should be held at the President’s pleasure. It is unquestionably an abuse to create a vacancy in the recess of the Senate, by turning a man out of office, and then filling it as a vacancy that has happened. . . . Shortly after the Convention met, there was a serious discussion on the importance of arranging a national system of sufficient strength to operate, in despite of State opposition, and yet not strong enough to break down State authority. I delivered on that occasion this short speech. ‘Mr President; if the rod of Aaron do not swallow the rods of the Magicians, the rods of the Magicians will swallow the rod of Aaron.’

In support of a broad interpretation of the clause

1. Debate in North Carolina Ratifying Convention, Speech of Archibald Maclaine

At the North Carolina ratification debate, Archibald Maclaine expressed his support for the Recess Appointments Clause. Recognizing that Congress would not always be in session, Maclaine believed that vesting the president with the recess appointments power was a crucial step in enabling the president to execute his duties and minimize governmental inconveniences.

“Congress are not to be sitting at all times; they will only sit from time to time, as the public business may render it necessary. Therefore the executive ought to make temporary appointments, as well as receive ambassadors and other public ministers. This power can be vested nowhere but in the executive, because he is perpetually acting for the public; for, though the Senate is to advise him in the appointment of officers, &c., yet, during the recess, the President must do his business, or else it will be neglected; and such neglect may occasion public inconveniences.”

2. The Federalist No. 67 (Alexander Hamilton)

Here, Hamilton underscores his belief that the Recess Appointments Clause was not the default appointing mechanism, and instead would act as a supplement to the preceding Appointments Clause.

“The last of these two clauses, it is equally clear, cannot be understood to comprehend the power of filling vacancies in the Senate, for the following reasons-First. The relation in which that clause stands to the other, which declares the general mode of appointing officers of the United States, denotes it to be nothing more than a supplement to the other; for the purpose of establishing an auxiliary method [of] appointment in cases, to which the general method was inadequate. The ordinary power of appointment is confided to the President and Senate jointly, and can therefore only be exercised during the session of the Senate; but as it would have been improper to oblige this body to be continually in session for the appointment of officers; and as vacancies might happen in their recess, which it might be necessary for the public service to fill without delay, the succeeding clause is evidently intended to authorise [sic] the President singly to make temporary appointments ‘during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which should expire at the end of their next session.’”

3. Letter from John Adams to James McHenry, April 16, 1799

Here, Adams wrote his Secretary of War, James McHenry, to address McHenry’s concern that Adams did not have the power to fill offices that first became vacant during a Senate session. McHenry’s concerns related to the president’s power to appoint “agents” to liaise between the Indian tribes and the American settlers, as authorized by the Act of March 3, 1799. In responding to McHenry’s doubts, Adams expressed his unfettered belief that the Constitution permitted him to use his recess appointment power to fill an office that became vacant during a Senate session. This interpretation also rejected Attorney General Randolph’s previously described interpretation of the Recess Appointments Clause as foreclosing the President from using his Recess Appointments power on appointments that arose while the senate was still in session. Nevertheless, despite Adams’ initial confidence in his ability to make a recess appointment to fill an office that first became vacant during a congressional session, Adams would later express doubt that he would be able to use his recess appointments power to fill vacancies occurring while Congress was in session.

“It is not upon the act of the 3d of March ultimo, that I ground the claim of an authority to appoint the officers in question, but upon the Constitution itself. Whenever there is an office that is not full, there is a vacancy, as I have ever understood the Constitution. To suppose that the President has power to appoint judges and ambassadors, in the recess of the Senate, and not officers of the army, is to me a distinction without difference…All such appointments, to be sure, must be nominated to the Senate at their next session, and subject to their ultimate decision. I have no doubt that it is my right and my duty to make the provisional appointments.”

4. 1 St. George Tucker, Blackstone’s Commentaries (1803)

St. George Tucker, an American legal scholar, is best known for his multi-volume annotated edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries, which detailed the incorporation of British common law into the early American legal system. Here, St. George Tucker contrasts offices that became vacant during the recess of the senate with offices “kept vacant” because of disagreements between the president and the senate. To St. George Tucker, the president would be able to utilize his power Recess Appointments power with the former, but the latter would require the office to be “kept vacant.”

“But if it should have happened that the office became vacant during the recess of the senate, and the vacancy were filled by a commission which should expire, not at the meeting of the senate, but at the end of their session, then, in case such a disagreement between the president and the senate, if the president should persist in his opinion, and make no other nomination, the person appointed by him during the recess of the senate would continue to hold his commission, until the end of their session: so that the vacancy would happen a second time during the recess of the senate, and the president consequently, would have the sole right of appointing a second time; and the person whom the senate have rejected, may be instantly replaced by a new commission. And thus it is evidently in the power of the president to continue any person in office, whom he shall once have appointed in the recess of the senate, as long as he may think proper. A circumstance which renders the power of nomination, and of filling up vacancies during the recess of the senate, too great to require any further extension.”

5. 3 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution §1551 (1833)

Though not in the original draft of the Constitution distributed on August 6, 1787, the Recess Appointments Clause was added by amendment without objection. Story explains the practical purpose of the Recess Appointments Clause. Providing the Executive with a temporary appointments power during Senate recesses furthered the Framers’ goal of an efficient and effective government. The deliberate limitations on the recess appointments power ensure that the executive does not usurp the senate’s role in the overall appointments process.

“§1551. There was but one of two course to be adopted; either, that the senate should be perpetually in session, in order to provide for the appointment of officers; or, that the president should be authorized to make temporary appointments during the recess…the former course would have been at once burthensome to the senate, and expensive to the public. The latter combines convenience, promptitude of action, and general security.”

(jump to the top of the page)

Instructions

Resolved: Can the President recess-appointment power be exercised during a recess that occurs within a session of the Senate?

Using historical materials related to the appointment clause, write an appellate brief arguing whether history does, or does not support the President’s power to make recess appointments during a session of the Senate. Further, also address whether the vacancy must have arisen during the recess.

Teams of two high school students will be responsible for writing an appellate brief on their class’s FantasySCOTUS blog. The Petitioner will argue that the President can make an appointment during a recess that occurs within a session, and the vacancy need not have arisen during the recess. The Respondent will argue that the President cannot make an appointment during a recess that occurs within a session,and the vacancy must occur during the recess.

The brief should have the following sections:

- Table of Cited Authorities: List all of the Supreme Court cases, original sources, and other documents you cite in your brief.

- Statement of Argument: State your position succinctly in 250 words or less.

- Argument: By relying on the history sources in this lesson plan, structure an argument about the scope of the President’s recess appointment power. The more authorities you cite, the stronger your argument will be–and the more likely your team will advance.

- Conclusion: Summarize your argument, and argue how the Supreme Court should decide National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning Corporation.

The brief should be submitted as a blog post by February 28, 2014. The brief must be a minimum of 2,000 words. For examples of what a complete Supreme Court brief should contain, see the Petitioner and Respondent briefs from last year’s competition regarding National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning Corporation. We recommend you develop your brief in Microsoft Word or Google Docs, and paste it into the blog post when you are finished. Be sure to proof read your work. The work must be yours, and you may not seek help from anyone else–including attorneys or law students. Students who submit plagiarized briefs will be disqualified.