Professor Kyle Graham graciously shared internal correspondences on the Court from Justice Blackmun’s papers regarding Smith v. Maryland. One of the more fascinating exchanges came in a series of letters between Justice Stevens, Justice Blackmun, and Blackmun’s law clerk AGL (Al Lauber, now a Tax Judge). If you ever wonder how those odd, out-of-place footnotes wind their way into majority opinions, this is it.

In short. Stevens urged Blackmun to clarify an issue about the subjective and objective expectation of privacy. Within a day, Blackmun’s clerk (who was given complete discretion on writing the opinion) managed to insert a footnote that repeated Stevens’s point very closely. Here’s the chronology.

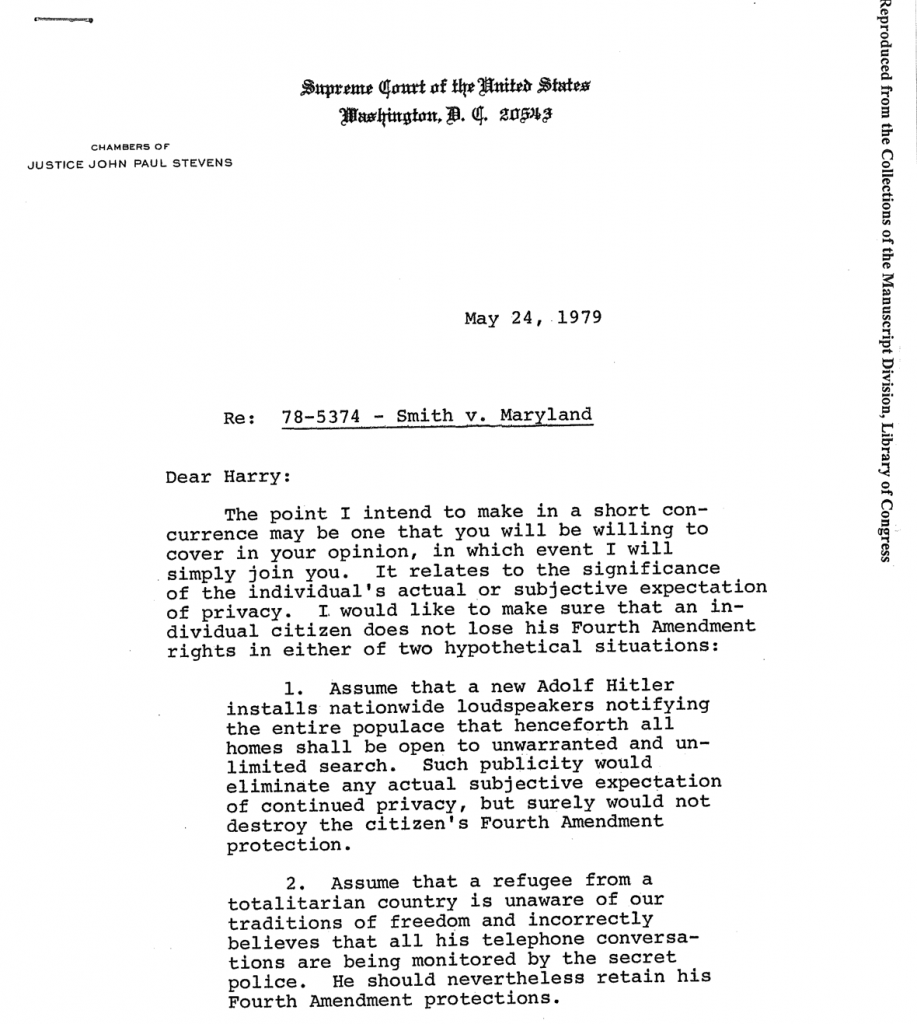

First on May 24, 1979 (two months after the case was argued on March 28, 1979), Stevens wrote to Blackmun regarding the “actual or subjective expectation of privacy,” offering two hypotheticals to consider.

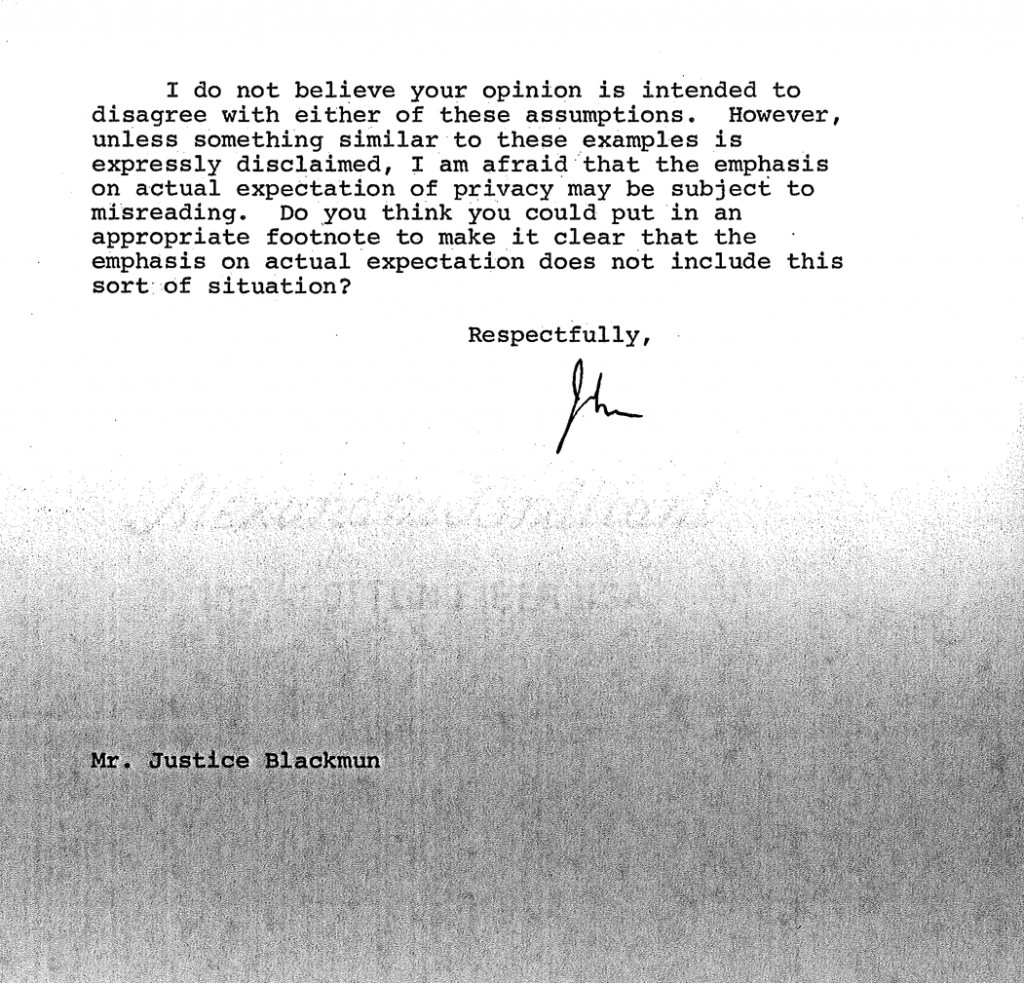

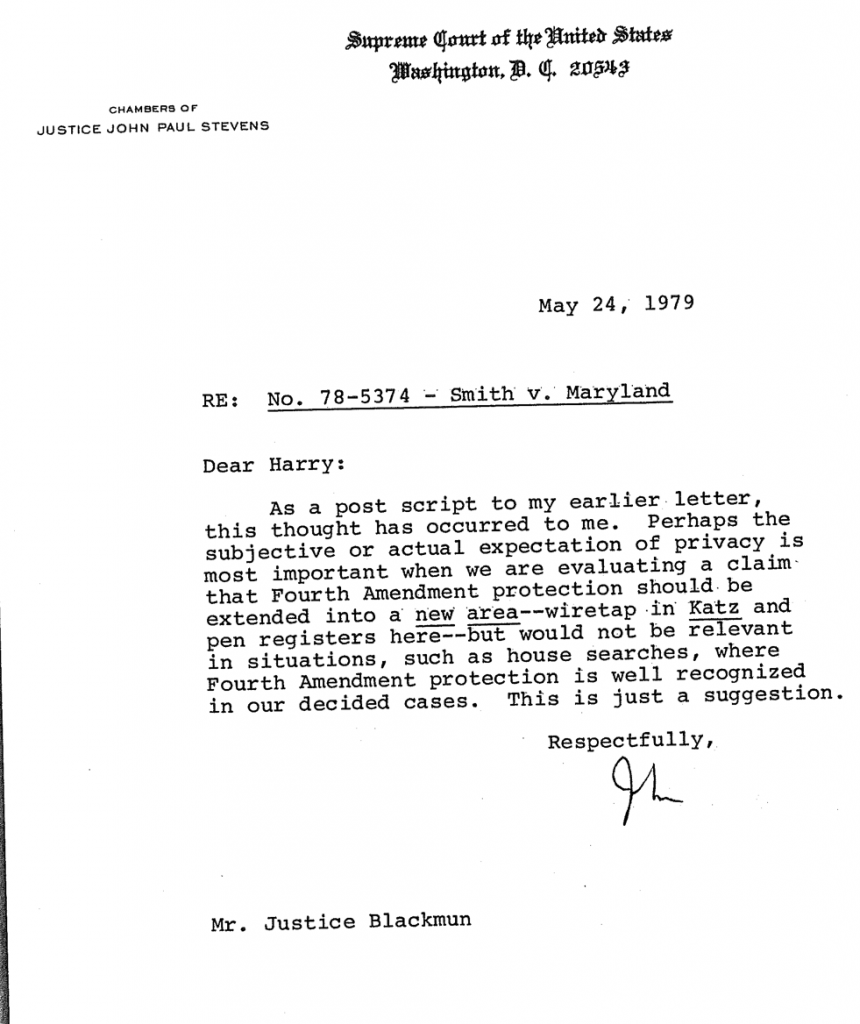

Later that day, Stevens sent a follow-up letter with a “suggestion” of how to treat the subjective and actual expectation of privacy when extending into a “new area.”

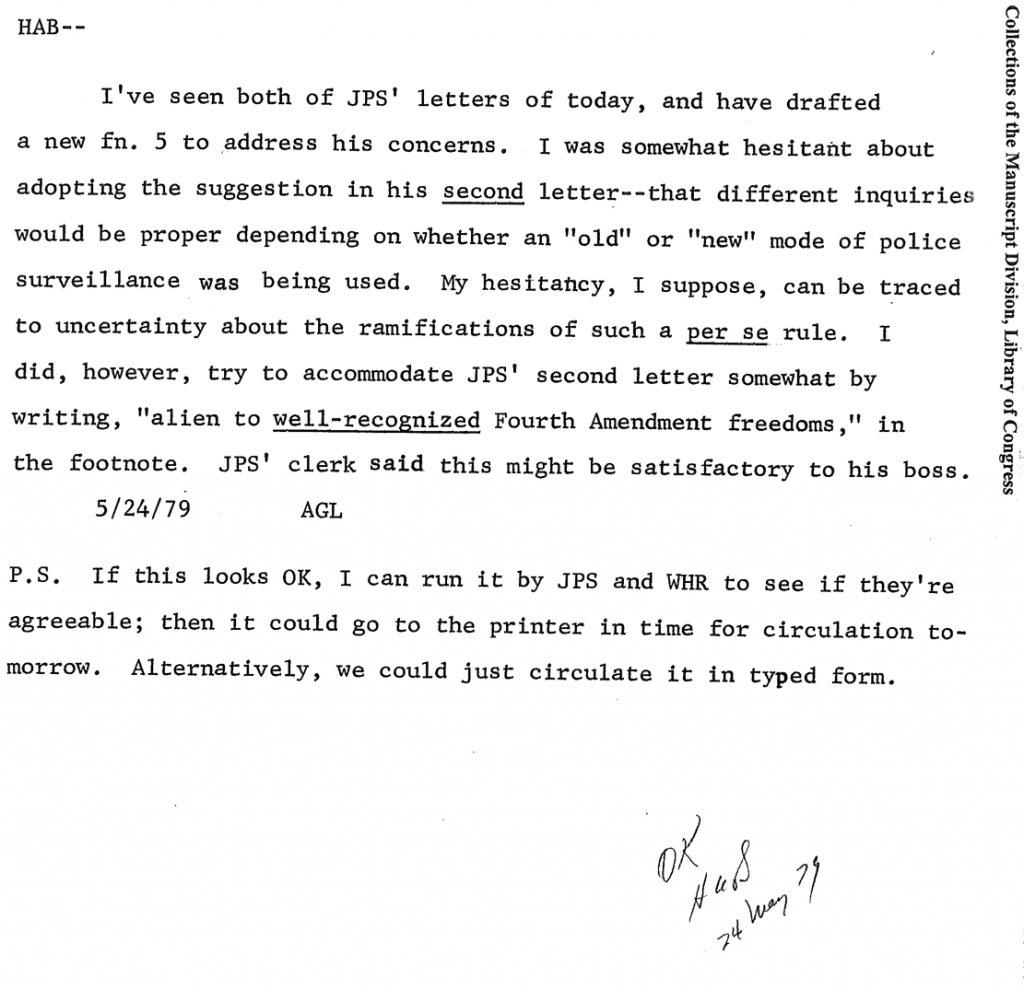

Later that day, Blackmun’s clerk, AGL, wrote back to Blackmun and offered a footnote to address JPS’s concern. HAB replied later that day “OK.”

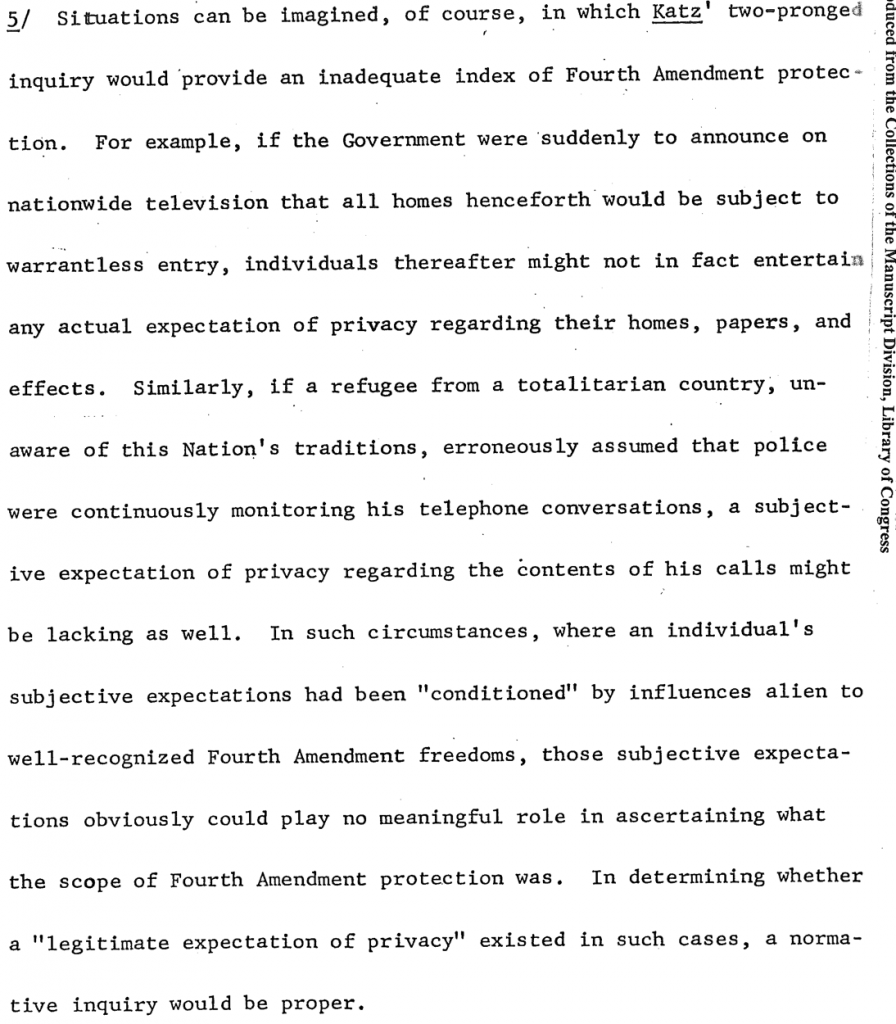

Here is the footnote inserted. You can see that it tracks JPS’s example very closely.

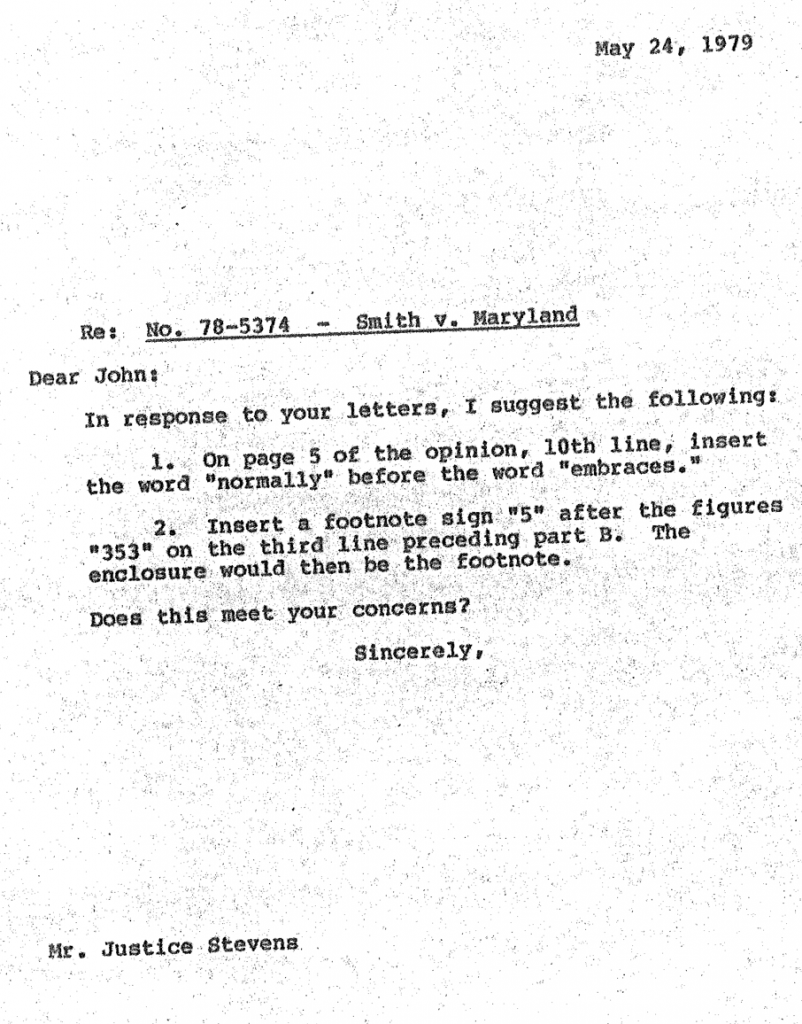

Blackmun wrote back to Stevens, asking if this footnote suffices.

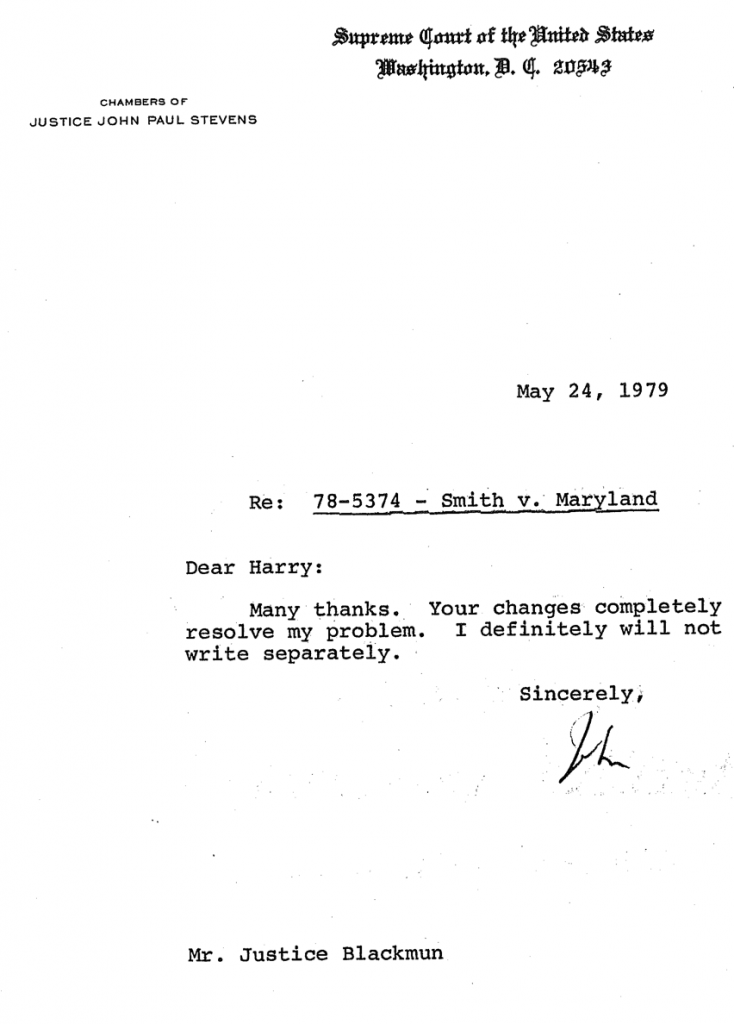

Stevens replied that it would do just fine, and he would not write separately.

Here is the final footnote 5 in Stevens v. Maryland.

[5] Situations can be imagined, of course, in which Katz’ two-pronged inquiry would provide an inadequate index of Fourth Amendment protection. For example, if the Government were suddenly to announce on nationwide television that all homes henceforth would be subject to warrantless entry, individuals thereafter might not in fact entertain any actual expectation of privacy regarding their homes, papers, and effects. Similarly, if a refugee from a totalitarian country, unaware of this Nation’s traditions, erroneously assumed that police were continuously monitoring his telephone conversations, a subjective expectation of privacy regarding the contents of his calls might be lacking as well. In such circumstances, where an individual’s subjective expectations had been “conditioned” by influences alien to well-recognized Fourth Amendment freedoms, those subjective expectations obviously could play no meaningful role in ascertaining what the scope of Fourth Amendment protection was. In determining whether a “legitimate expectation of privacy” existed in such cases, a normative inquiry would be proper.

Fascinating.

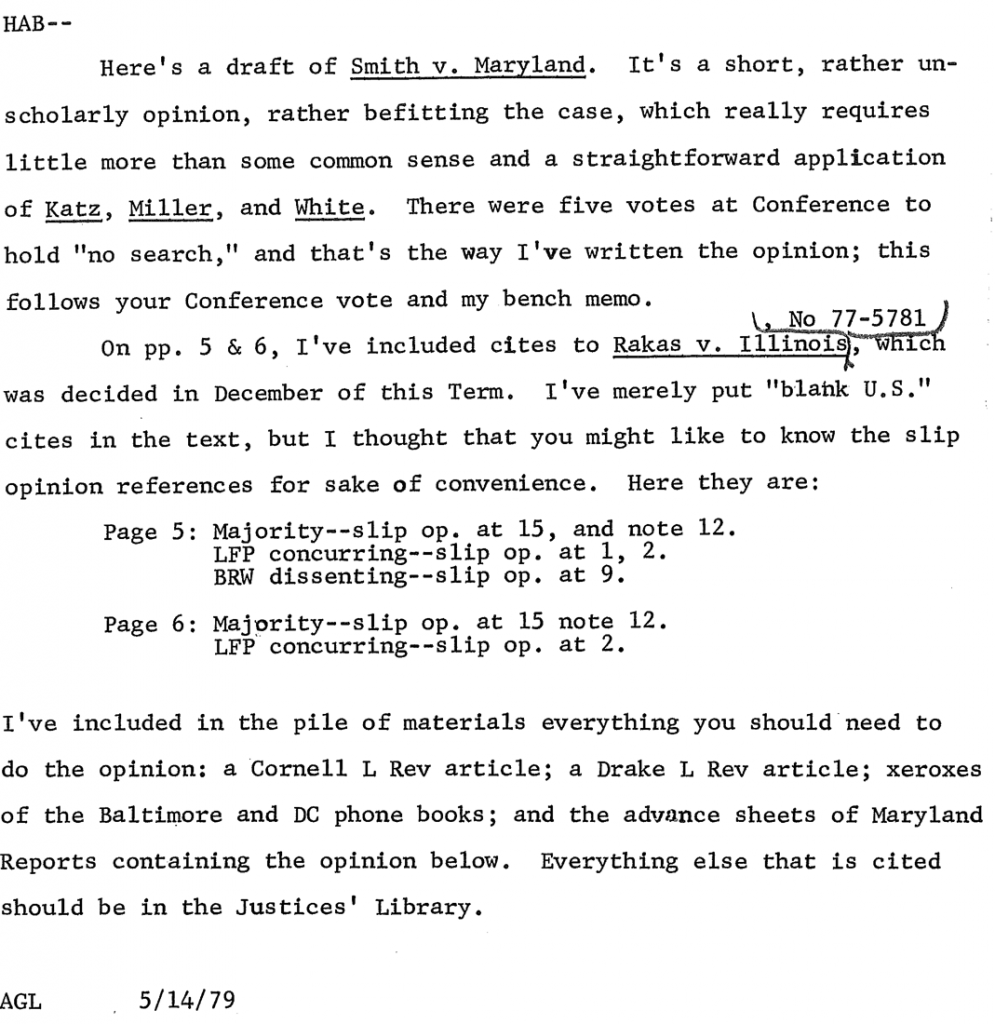

Update: To respond to a question on Twitter, it was fairly common for Justice Blackmun to delegate the task of writing opinions entirely to the clerk. Here is the clerk’s transmittal memo, noting how he wrote the “short, rathe unscholarly opinion, rather befitting the case.”