This is a great story.

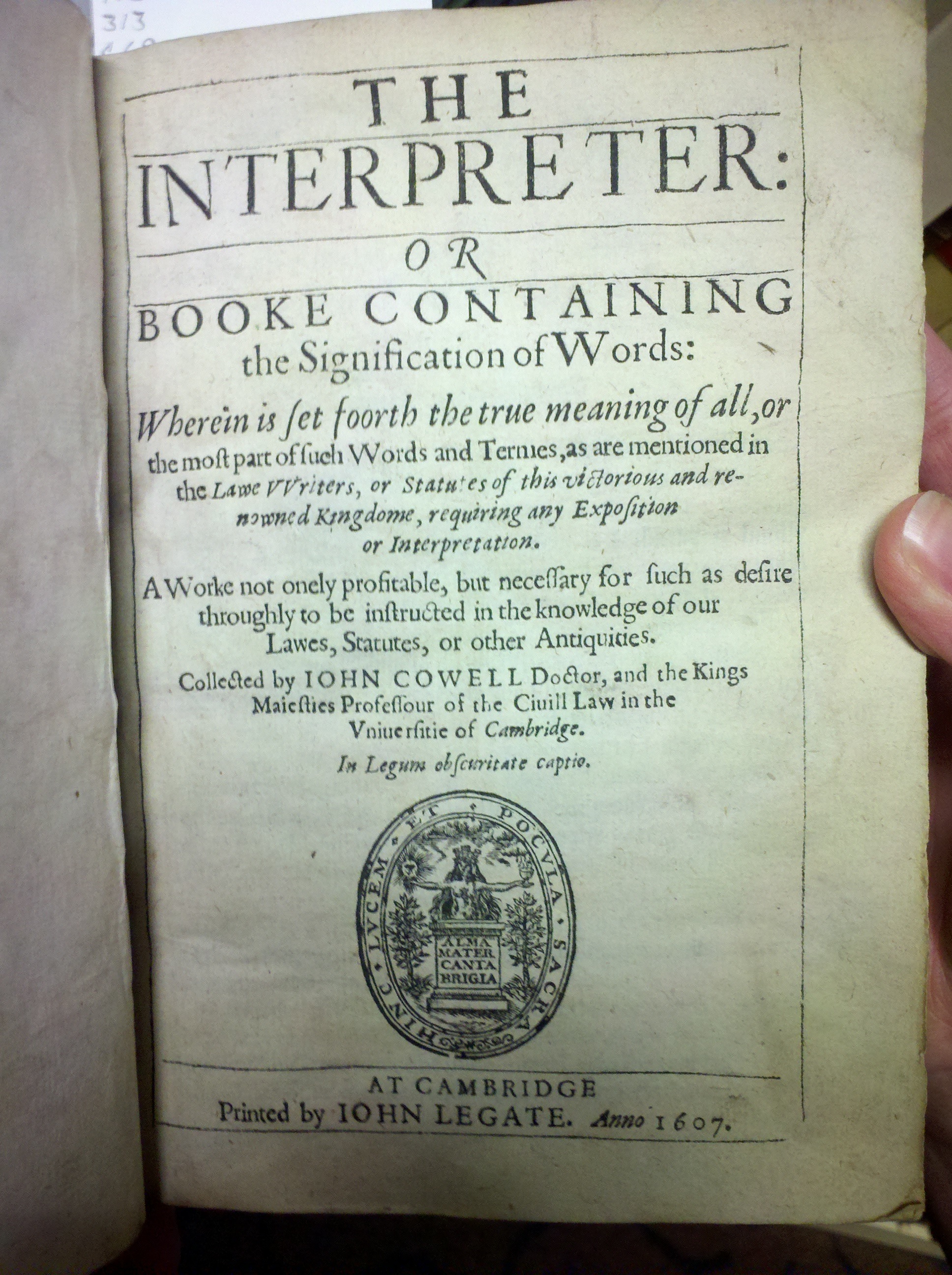

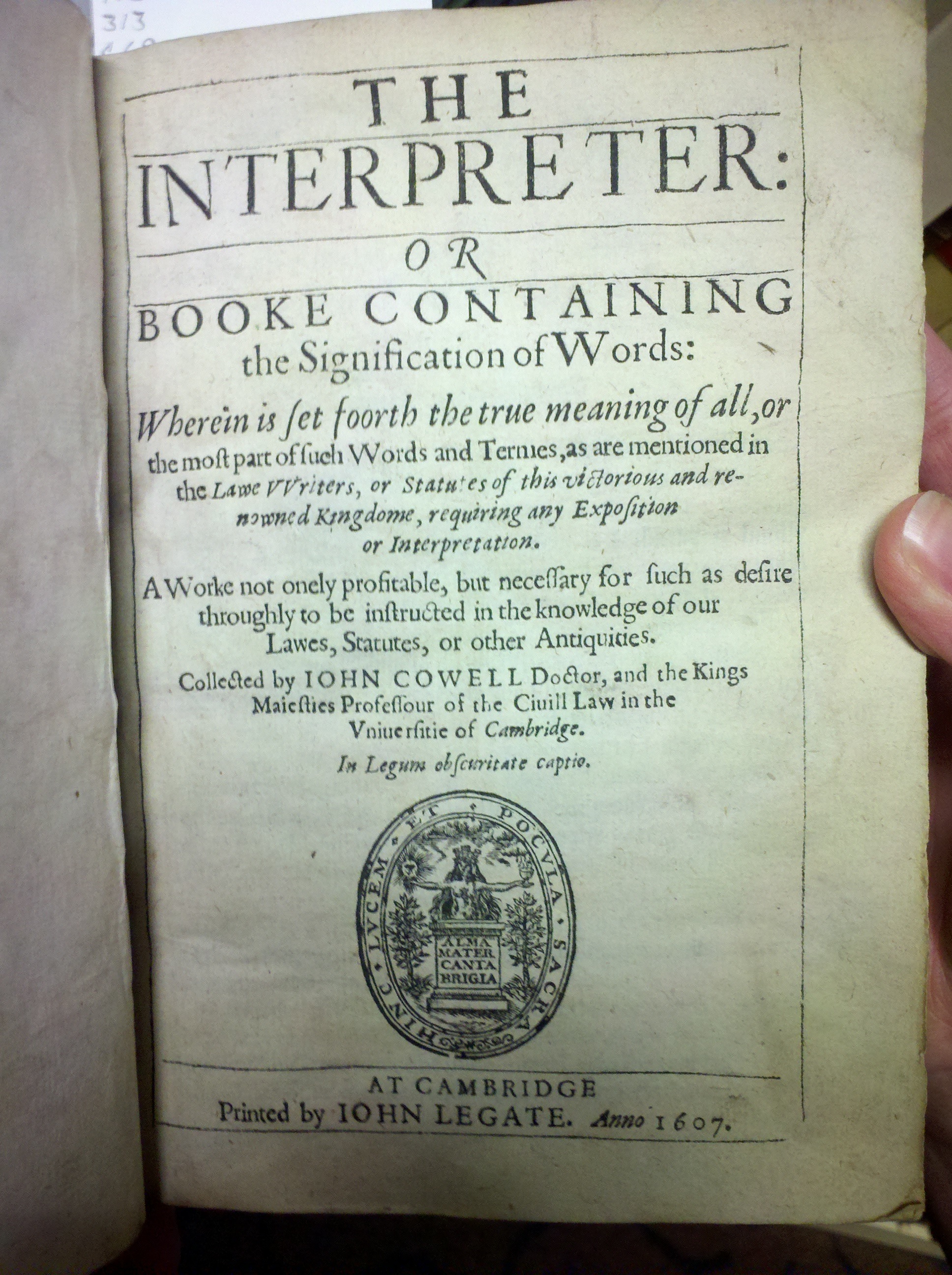

The Interpreter, first published in 1607 by John Cowell, was one of the first law dictionaries in English. Cowell was a civil law professor at Cambridge. The full title is “The Interpreter: Or Booke Containing the Signification of Words: Wherein is Set Forth the True Meaning of All, or the Most Part of Such Words and Termes, as are Mentioned in the Law Writers, or Statutes of This Victorious and Renowned Kingdom, Requiring Any Exposition or Interpretation. A Work not Onely Profitable, but Necessary for Such as Desire Throughly to be Instructed in the Knowledge of Our Laws, Statutes, and Other Antiquities.”

The South Texas Library has an original copy of the Interpreter in its archives, with an original printing date of 1607. Amazingly, this document is roughly equal in time from Magna Carta (393 years) and the Present (405 years).

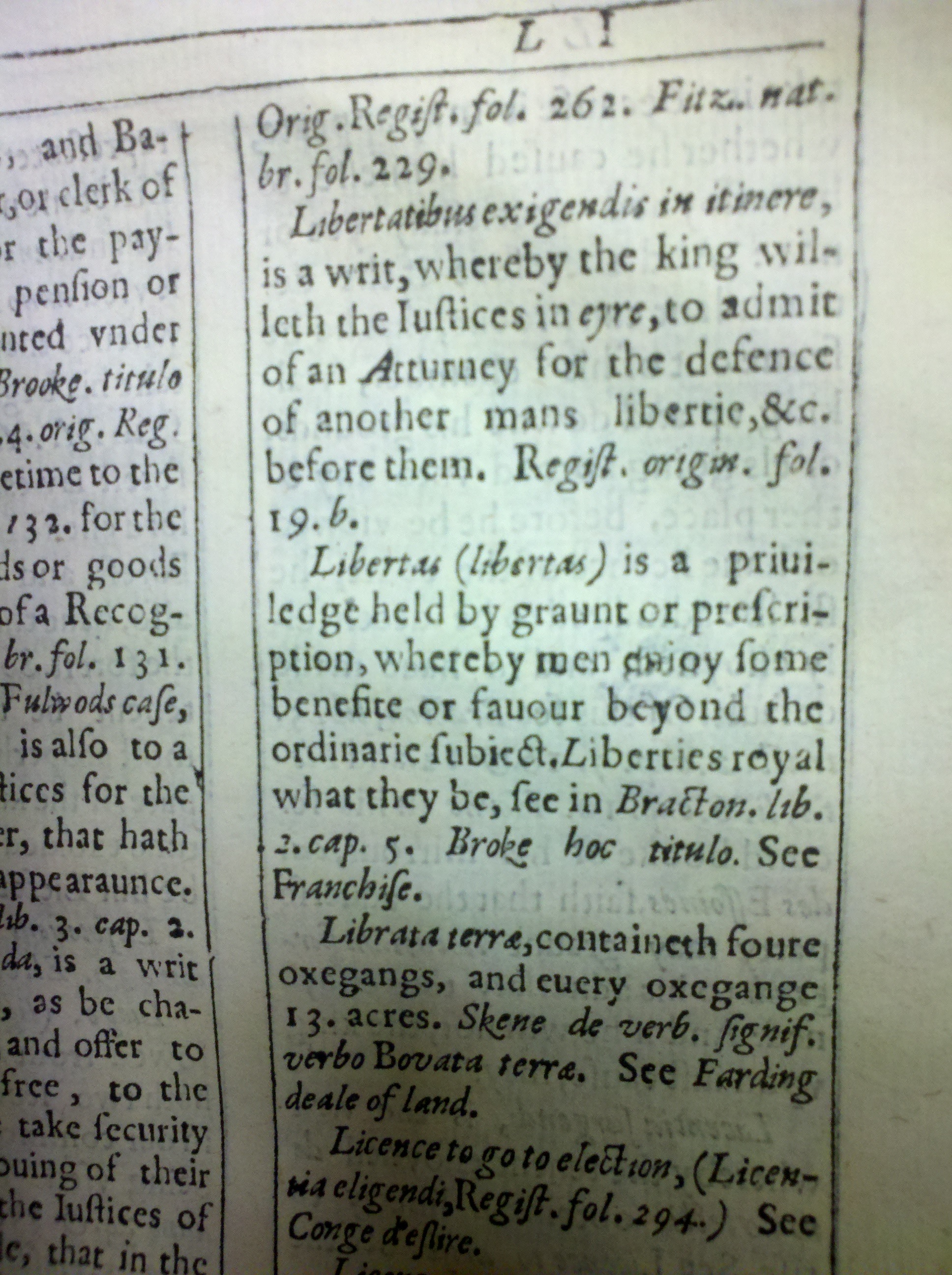

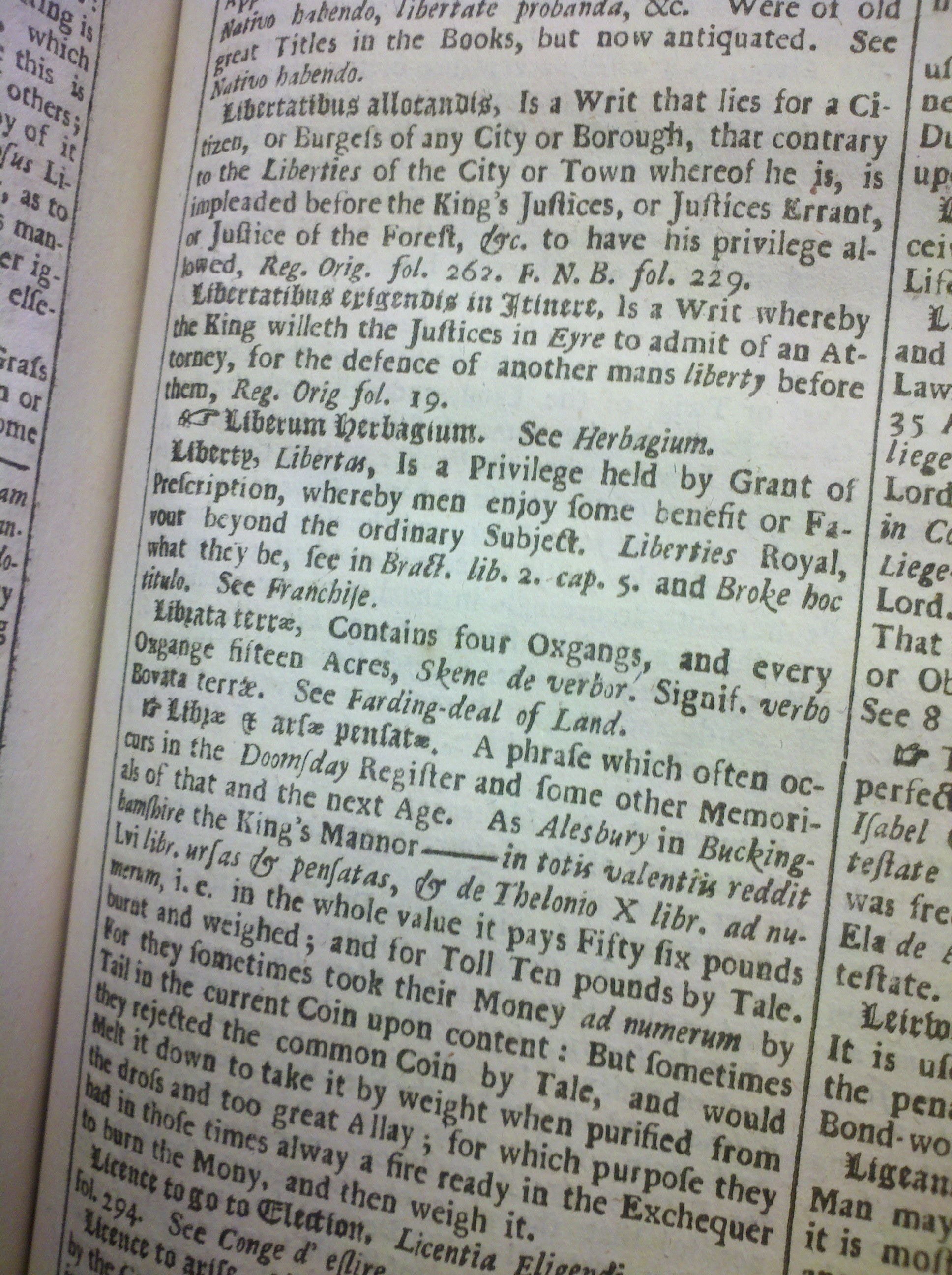

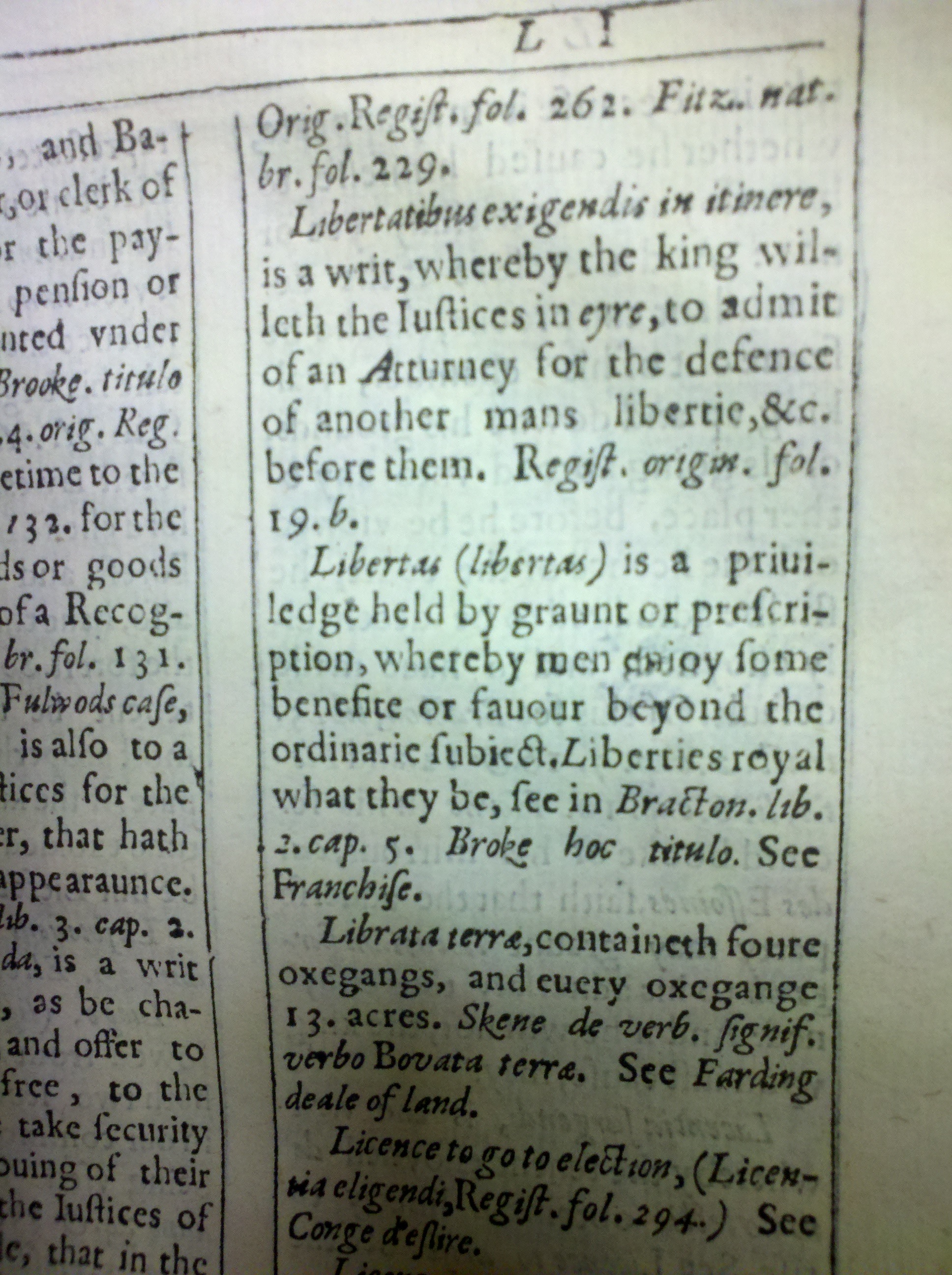

So of course the first thing I do is look up the definition of the word liberty.

LIbertas (libertas) is a priuiledge [privilege] held by graunt or prescription, whereby men enjoy some benefite or fauour [favor] beyond the ordinarie subject, Liberties royal what they be, see in Bracton. lib. 2. cap. 5. Broke hoc titulo. See Franchise.

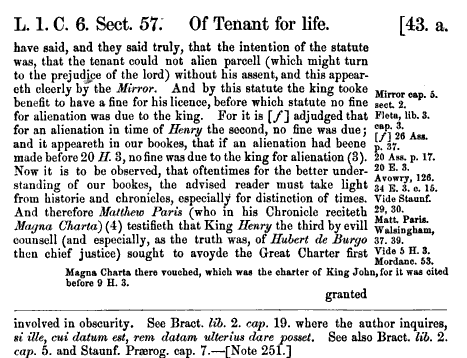

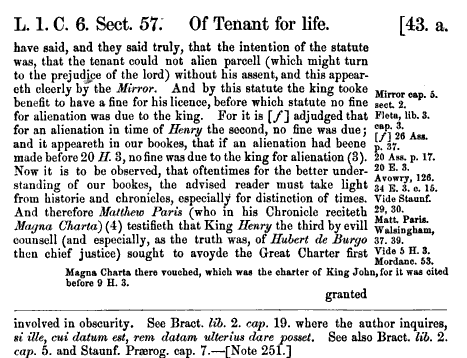

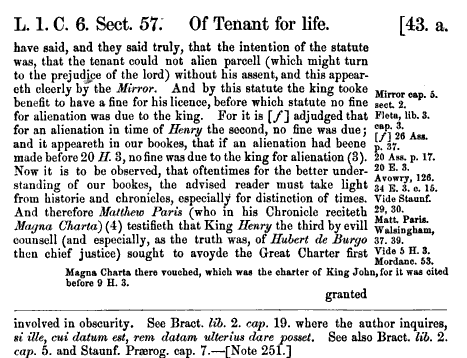

Bract. refers to Bracton on the Laws and Customs of England. Interestingly, I found a citation to that same chapter in Coke’s Institute’s which were published between 1628 and 1644. The Interpreter came first.

Coke cited this passage in a section talking about feudal property law and Magna Carat.

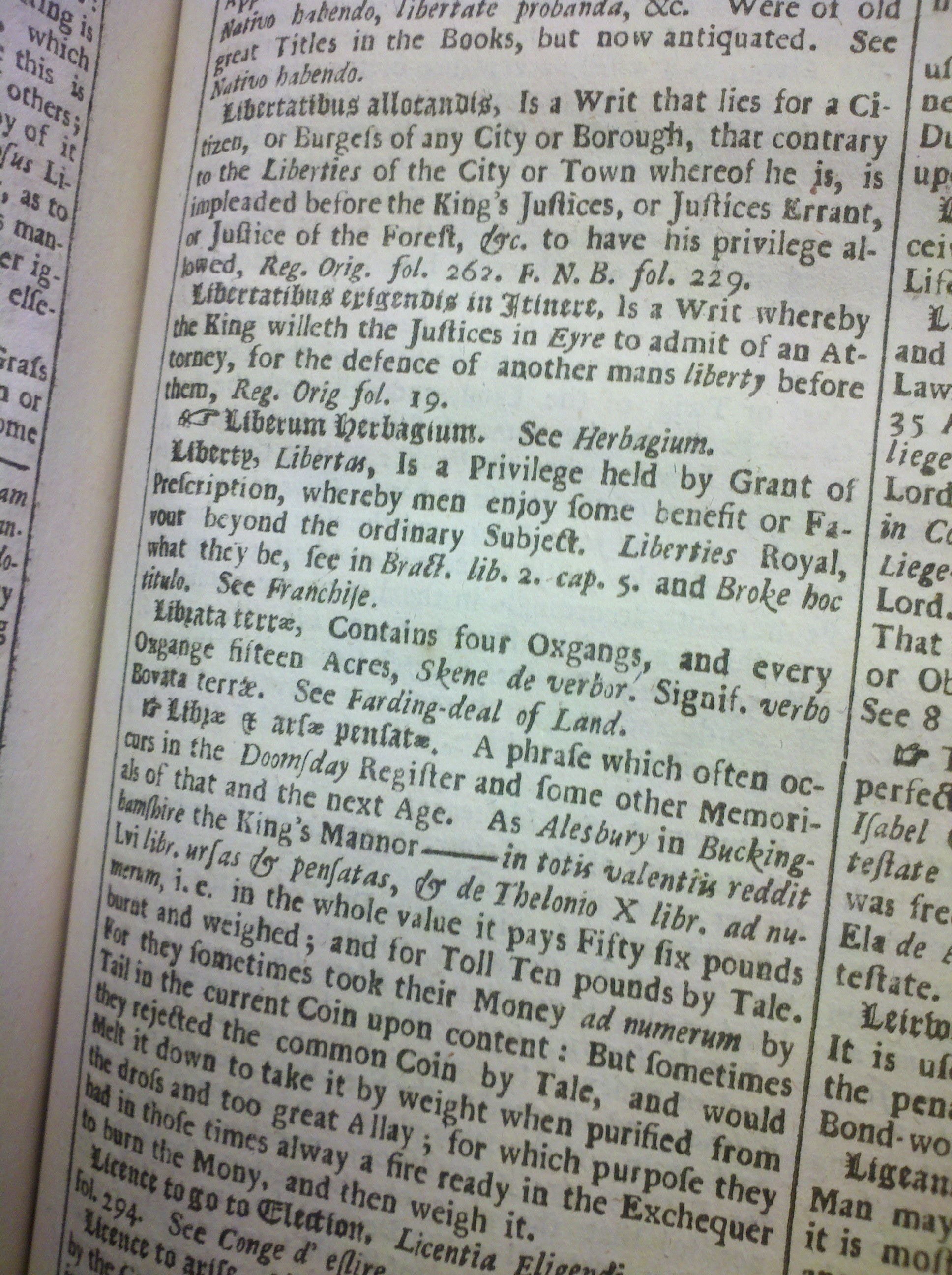

A later version of The Interpreter, which the library also has a copy of, from 1708 has a mostly similar definition of liberty, though it is referred to as “liberty” as well as “libertas.” Also, the spelling has become more consistent with how we spell today.

Liberty, Libertas, Is a Privilege held by Grant or Prescription, whereby men enjoy some benefit or Favour beyond the ordinary subject. Liberties Royal, what they be, see in Bract. lib. 2. cap. 5 and Broke hoc titule. See Franchise.

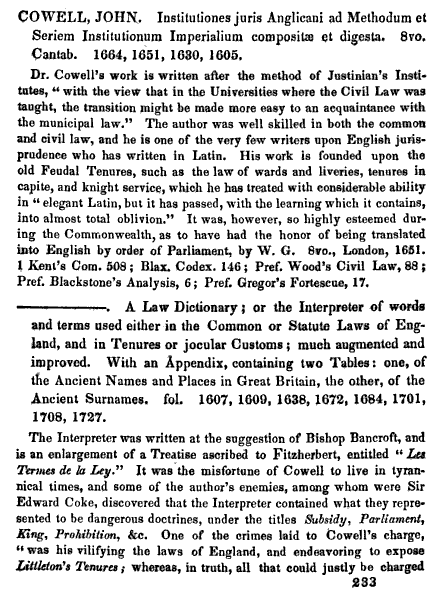

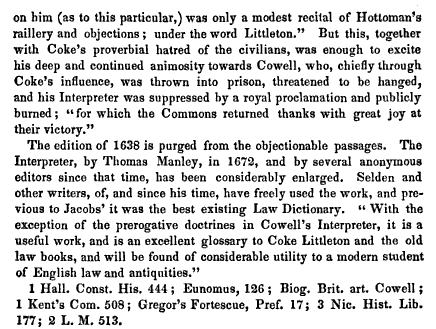

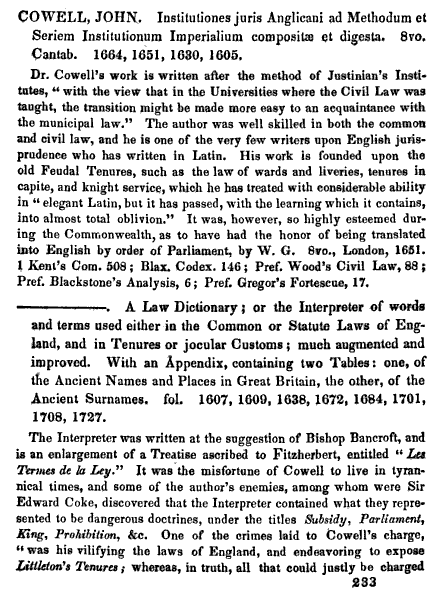

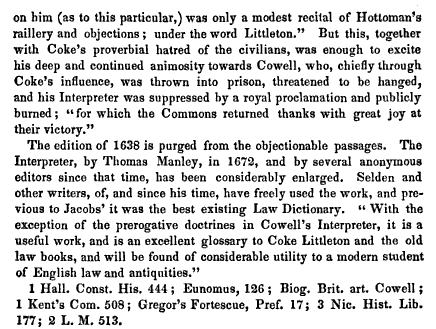

From Legal bibliography, or a thesaurus of American, English, Irish, and Scotch law books: together with some continental treatises. Interspersed with critical observations upon their various editions and authority. To which is prefixed a copious list of abbreviations (1847), of which the school also has an original copy, we learn a fascinating fact–this book was banned! By Sir Edward Coke, who used the same citation to Brachton for liberty!

“Sir Edward Coke, discovered that the Interpreter contained what they represented to be dangerous doctrines under the titles, Subsidy, Parliament, King, Prohibition, &c.” Cowell was charged with “villifying the laws of England and endeavoring to expose Littletons’ Tenures; whereas, in truth, all that could justly be charged on him (as to this particular) was only a modest recital of Hottomans’ raillery and objections. But this, together with Coke’s proverbial hatred of the civlians was enough to excite his deep and continued animosity towards Cowell, who, chiefly through Coke’s influence, was thrown into prison, threatened to be hanged, and his Interpreter was suppressed by a royal proclamation and publicly burned; for which the Commons returned thanks with great joy at their victory.”

Coke is burning books! Wow!

William Holdsworth wrote that King James I suppressed the book in support of Coke and other common law lawyers, who it seems did not like the Civil-law inspired digest, based on Justinian.

“Cowell follows exactly the order and books of the Justinian Institutesand forces the English material into this exotic mold….

“Unfortunately, the (Interpreter) trespassed upon the domain of politics by expressing pronounced absolutist views in its definitions of Prerogative, Parliament and Subsidie….

“Coke and the common law lawyers … combined with the constitutional opposition to attack Cowell and his book and James I thought it politic to disown him. The book was suppressed by Royal proclamation.”

Julius Marke wrote:

“Its publication provoked controversy. At a time when Parliament and crown were vying for power, the Commons disapproved of Cowell’s royalist sympathies, which were evident in such definitions as “King,” “Parliament,” “Prerogative,” “Recoveries” and “Subsidies.” When a joint committee of Lords and Councilors reviewed the work, the ensuing controversy nearly halted the affairs of government….

“James I intervened in fear that his own fiscal interests would not be approved by Parliament. Encouraged by Coke, the king imprisoned Cowell, suppressed the book and ordered all copies burned by a public hangman on March 10, 1610 (Ed. note: correct date is 26 March). Moreover, The Interpreter contained a quotation that criticized Littleton’s scholarship, which alienated and enraged Sir Edward Coke. It comes as no surprise that he was instrumental in the book’s suppression and in Cowell’s persecution.”

Here is the indictment:

“Anno 7 Jacobi, 1909, Dr. Cowell, Professor of the Civil Law at Cambridge, writ a book called The Interpreter, rashly, dangerously and perniciously asserting certain heads to the overthrow and destruction of Parliaments, and the fundamental laws and government of the Kingdom.”

Treason for publishing a dictionary. Bryan Garner would not have been so prolific back in the day…

This was all a battle between the common law courts and civil law courts.

Good thing a copy of the original, banned version from 1607 survived. Here is how Parliament and Perogative of the King are defined:

“Parliament: A solemn conference of all the states of the kingdom summoned together by the Kings only authority to treat of the weighty affairs of the realm.

“Prerogative of the King: That special power, preeminence or privilege which the king hath over and above other persons and above the ordinary course of the common law in the right of his crown.”

Thanks to Heather Kushnerick, the Special Collections Librarian at South Texas for showing me this gem and providing me with information about the history of the book.