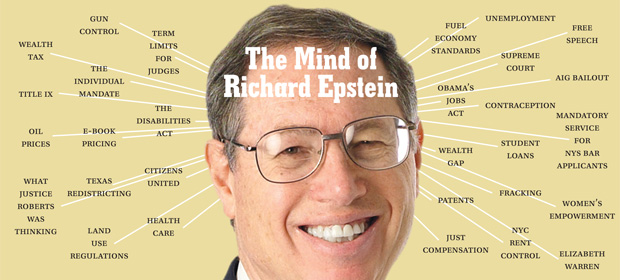

The Times has a great piece about the history of Grand Central State, the situs of the famous Penn Central v. New York. There is an interesting discussion about the decision not to build office space atop the building. This choice, ultimately, led to Penn Central.

In 1903, the Central invited the nation’s leading architects to submit designs for the new terminal. Samuel Huckel Jr. went for baroque, a turreted confection with Park Avenue slicing through it. McKim, Mead & White proposed a 60-story skyscraper — the world’s tallest — atop the terminal (a modified version was later incorporated into the firm’s design for the 26-story municipal building, completed in 1916), itself topped by a dramatic 300-foot jet of steam illuminated in red as a beacon for ships and an advertisement (if, even then, an anachronistic one) for the railroad.

Reed & Stem, a St. Paul firm, won the competition. The firm began with two big advantages. It had designed other stations for the New York Central. Moreover, like the Central itself, Reed & Stem could count on connections: Allen H. Stem was Wilgus’s brother-in-law. Yet in the highly charged world of real estate development in New York, another firm’s connections trumped Reed & Stem’s. After the selection was announced, Warren & Wetmore, who were architects of the New York Yacht Club and who boasted society connections, submitted an alternative design. It didn’t hurt that one of the firm’s principals, Whitney Warren, was William Vanderbilt’s cousin.

The Central’s chairman officiated at a shotgun marriage of the two firms, pronouncing them the Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal. The partnership would be fraught with dissension, design changes and acrimony and would climax two decades later in a spectacular lawsuit and an appropriately monumental settlement.

To Wilgus’s dismay, the Warren & Wetmore version eliminated the revenue-generating office and hotel tower atop the terminal. It also scrapped proposed vehicular viaducts to remedy the obstruction of Fourth Avenue, now Park, created by the depot.

A 300 foot red jet of steam? That would’ve been something.

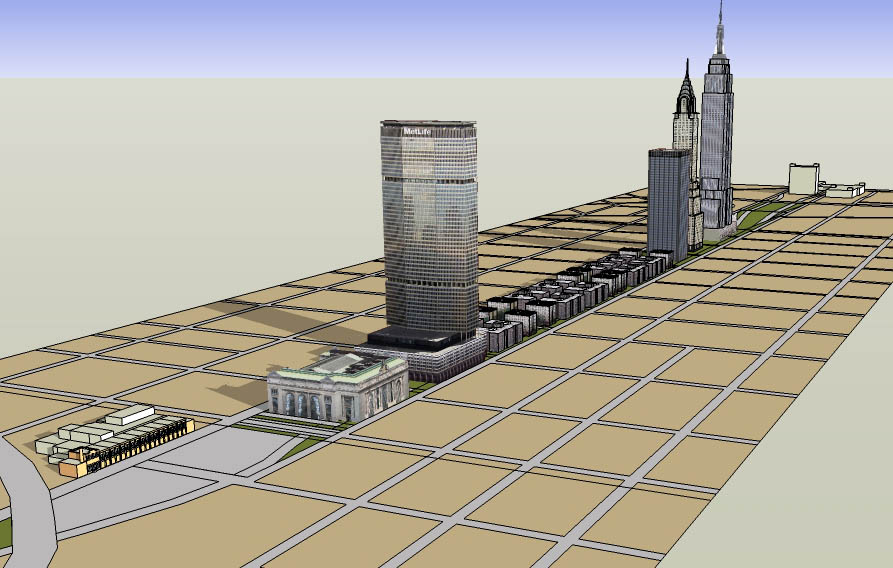

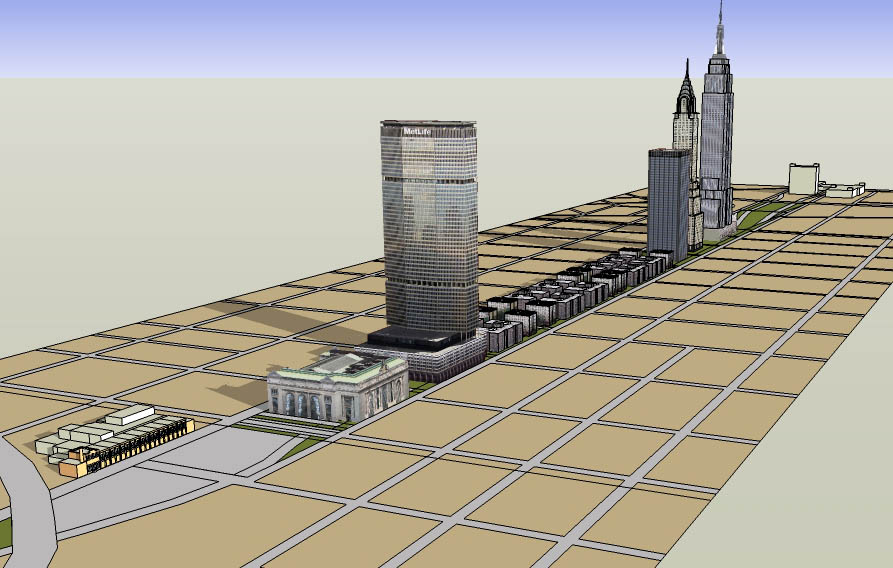

Here are the designs for adding a skyscraper to Grand Central Station in the 1960s. These, were of course, never built. To give you a sense of where Grand Central is, and how the later redesign would have fit into the city, this diagram is helpful:

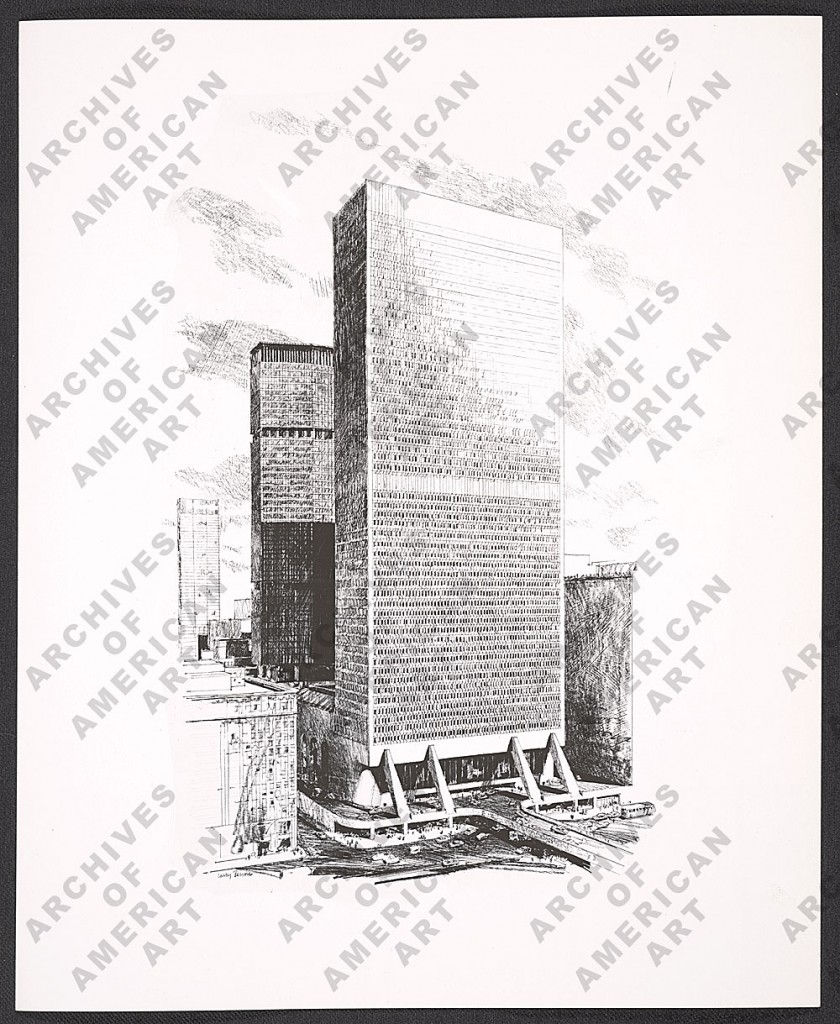

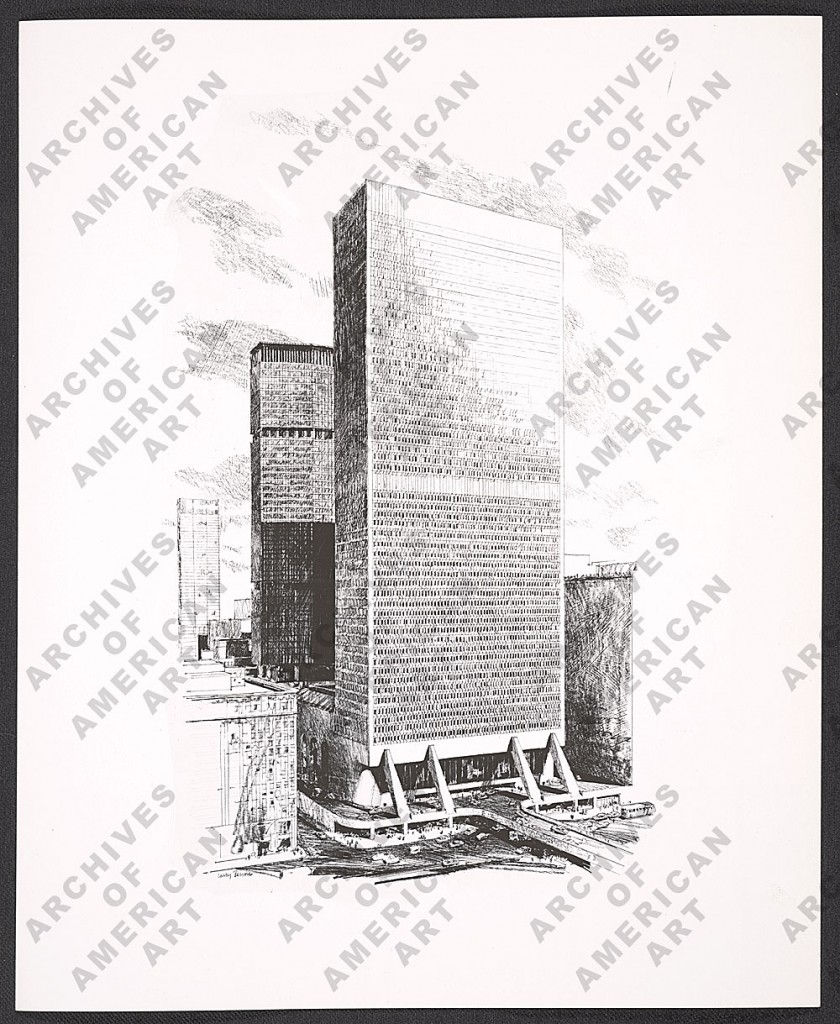

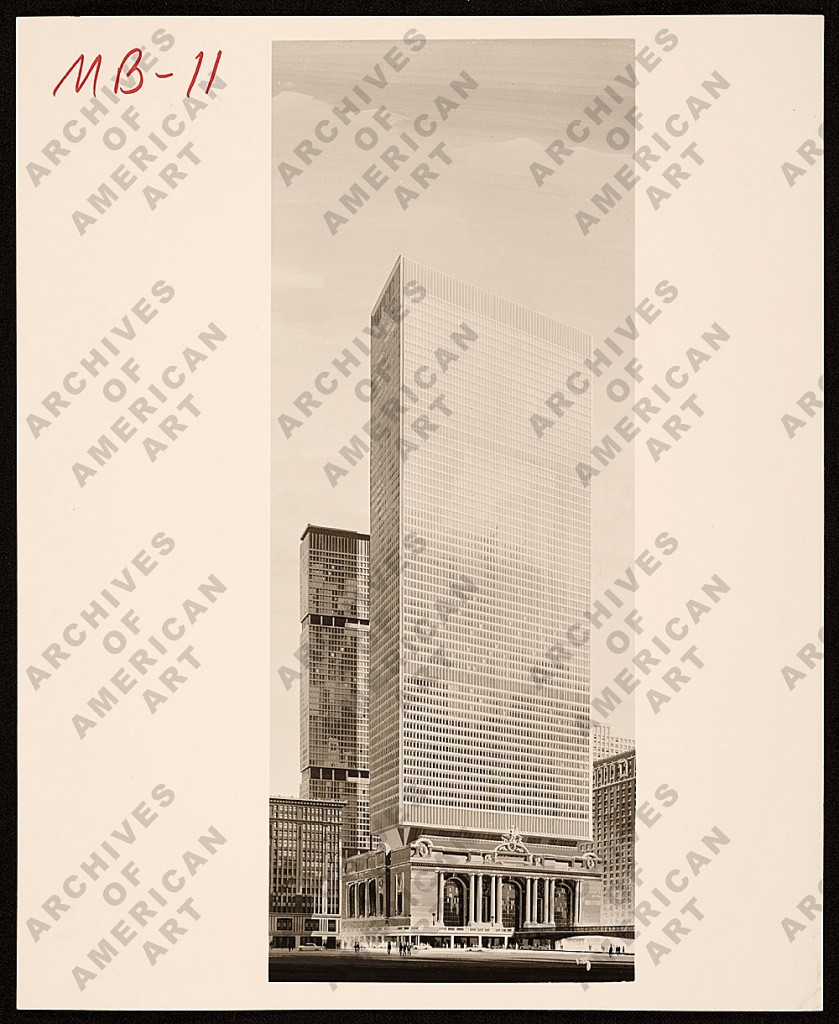

Here are blueprints of the two proposed designs to build above Grand Central. The first design, Breur I, would have preserved the exterior and built a tower. “The first, Breuer I, provided for the construction of a 55-story office building, to be cantilevered above the existing facade and to rest on the roof of the Terminal.”

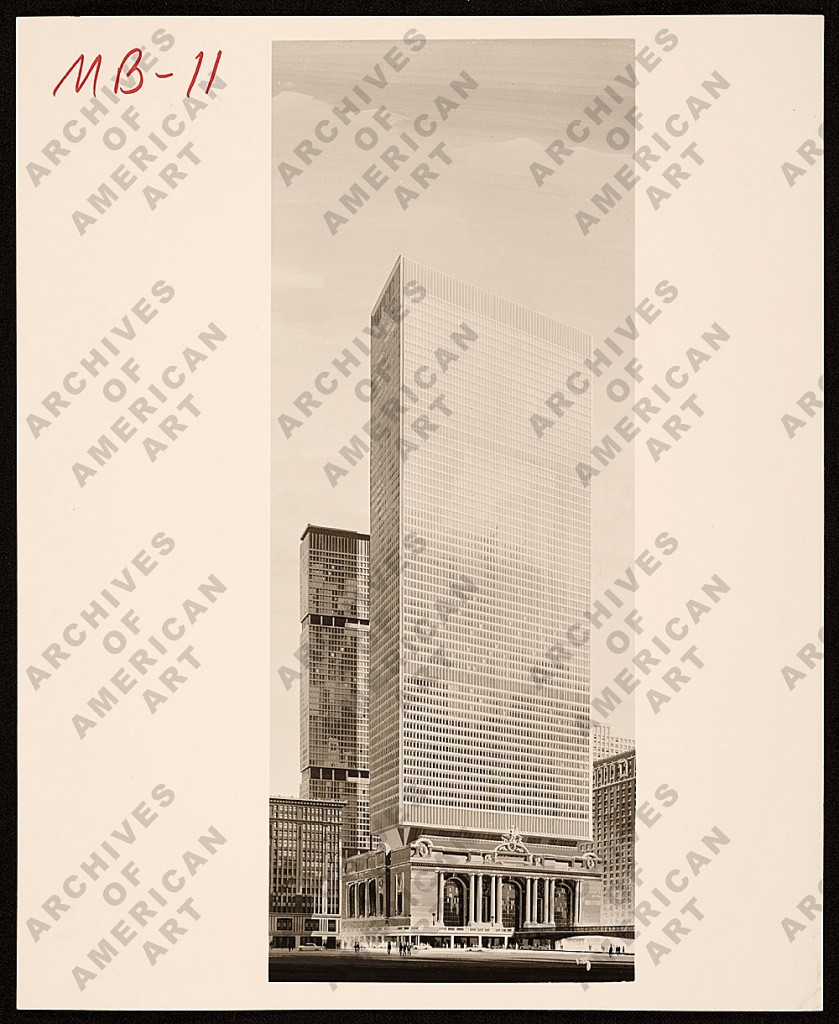

The second design, Breur II, would have stripped the facade and built the tower. “The second, Breuer II Revised, called for tearing down a portion of the Terminal that included the 42d Street facade, stripping off some of the remaining features of the Terminal’s facade, and constructing a 53-story office building.”